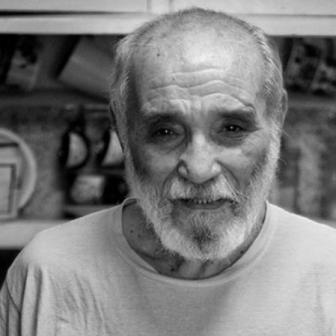

Rafael Alcides

LETTER TO RUBÉN

My son,

meal and tender

of my tenderness,

lightest of all angels:

from today on

you are the exiled one,

who sets the table under other skies

and makes his bed

wherever he can,

who awakes in deep night

terrified and rushes

in the morning

to look under the door

for a possible letter

that might for a moment

return him to the neighborhood,

the street, the house

where joy flowed like a river,

the dog, the cat,

the smell of Sunday dinners,

everything good and eternal,

the only eternity

of all that was lost

back there, far away,

when the plane like a sad bird

left, saying goodbye;

he who wanders and dreams

as a stranger far from the fatherland,

tolerated, and at times,

with some luck, a protégé

to whom people give overcoats

and shoes they were going to throw away.

But we,

alone and sad,

grieving,

half dead,

who have seen the plane fly away

--without knowing if it will return

or if we'll be alive when it does--

we the hapless ones

who smoke and grow old

and take sedatives

waiting for the mailman,

we--where,

where?

What country are we in now?

The country far from all that is loved?

The country where a place setting is missing from the table,

where there is always an extra bed. . .?

My child who wound up so far away,

God and I and the mockingbird

that sang by the window know:

the place where one lives amid firing squads and deadbolts

is also an exile. And thus,

with a diamond ring

or a hammer in our hand,

all of us born here are exiles. All of us.

Those who left

and those who stayed behind.

And there aren't

words in our language

or movies on earth

to make the accusation:

millions of mutilated beings

exchanging kisses, memories and sighs

across the sea.

Call,

son. Write.

Send me a photo.

CARTA A RUBÉN

CARTA A RUBÉN

Hijo mío,

harina, ternura

de mis ternuras,

ángel mas leve que los ángeles:

desde hoy en adelante

eres el exiliado,

el que bajo otros cielos

organiza su cama y su mesa

donde puede,

el que en la alta noche

despierta asustado y presuroso

corre por la mañana

a buscar debajo de la puerta

la posible carta

que por un instante

le devuelva el barrio,

la calle, la casa

por donde pasaba la dicha como un río,

el perro, el gato,

el olor de los almuerzos del domingo,

todo lo bueno y eterno,

lo único eterno,

cuanto quedó perdido

allá atrás, muy lejos

cuando el avión como un pájaro triste

se fue diciendo adiós.

El que deambula y sueña

lejos de la patria, el extraño,

el tolerado --y, a veces,

con suerte, el protegido

al que se le regalan los abrigos

y los zapatos que se iban a botar.

Pero nosotros,

nosotros los solos,

los tristes,

los luctuosos,

los que medio muertos

hemos visto partir el avión

-sin saber si volverá

o si estaremos vivos por entonces-,

nosotros, esos desventurados

que fuman y envejecen

y consumen barbitúricos,

esperando al cartero,

nosotros, ¿dónde,

adónde,

en qué patria estamos ahora?

¿La patria lejos de lo que se ama. . .?

¿La patria donde falta un cubierto a la mesa,

donde siempre sobra una cama. . .?

Dios y yo y el sinsonte

que cantaba en la ventana

lo sabemos, niño mío que fuiste a dar tan lejos:

donde se vive entre paredones y cerrojos

también es el exilio. Y así,

con anillo de diamantes

o martillo en la mano,

todos los de Acá

somos exiliados. Todos.

Los que se fueron

y los que se quedaron.

Y no hay, no hay

palabras en la lengua

ni películas en el mundo

para hacer la acusación:

millones de seres mutilados

intercambiando besos, recuerdos y suspiros

por encima de la mar.

Telefonea,

hijo. Escribe.

Mándame una foto.

LETTER TO RUBÉN

My son,

meal and tender

of my tenderness,

lightest of all angels:

from today on

you are the exiled one,

who sets the table under other skies

and makes his bed

wherever he can,

who awakes in deep night

terrified and rushes

in the morning

to look under the door

for a possible letter

that might for a moment

return him to the neighborhood,

the street, the house

where joy flowed like a river,

the dog, the cat,

the smell of Sunday dinners,

everything good and eternal,

the only eternity

of all that was lost

back there, far away,

when the plane like a sad bird

left, saying goodbye;

he who wanders and dreams

as a stranger far from the fatherland,

tolerated, and at times,

with some luck, a protégé

to whom people give overcoats

and shoes they were going to throw away.

But we,

alone and sad,

grieving,

half dead,

who have seen the plane fly away

--without knowing if it will return

or if we'll be alive when it does--

we the hapless ones

who smoke and grow old

and take sedatives

waiting for the mailman,

we--where,

where?

What country are we in now?

The country far from all that is loved?

The country where a place setting is missing from the table,

where there is always an extra bed. . .?

My child who wound up so far away,

God and I and the mockingbird

that sang by the window know:

the place where one lives amid firing squads and deadbolts

is also an exile. And thus,

with a diamond ring

or a hammer in our hand,

all of us born here are exiles. All of us.

Those who left

and those who stayed behind.

And there aren't

words in our language

or movies on earth

to make the accusation:

millions of mutilated beings

exchanging kisses, memories and sighs

across the sea.

Call,

son. Write.

Send me a photo.

LETTER TO RUBÉN

My son,

meal and tender

of my tenderness,

lightest of all angels:

from today on

you are the exiled one,

who sets the table under other skies

and makes his bed

wherever he can,

who awakes in deep night

terrified and rushes

in the morning

to look under the door

for a possible letter

that might for a moment

return him to the neighborhood,

the street, the house

where joy flowed like a river,

the dog, the cat,

the smell of Sunday dinners,

everything good and eternal,

the only eternity

of all that was lost

back there, far away,

when the plane like a sad bird

left, saying goodbye;

he who wanders and dreams

as a stranger far from the fatherland,

tolerated, and at times,

with some luck, a protégé

to whom people give overcoats

and shoes they were going to throw away.

But we,

alone and sad,

grieving,

half dead,

who have seen the plane fly away

--without knowing if it will return

or if we'll be alive when it does--

we the hapless ones

who smoke and grow old

and take sedatives

waiting for the mailman,

we--where,

where?

What country are we in now?

The country far from all that is loved?

The country where a place setting is missing from the table,

where there is always an extra bed. . .?

My child who wound up so far away,

God and I and the mockingbird

that sang by the window know:

the place where one lives amid firing squads and deadbolts

is also an exile. And thus,

with a diamond ring

or a hammer in our hand,

all of us born here are exiles. All of us.

Those who left

and those who stayed behind.

And there aren't

words in our language

or movies on earth

to make the accusation:

millions of mutilated beings

exchanging kisses, memories and sighs

across the sea.

Call,

son. Write.

Send me a photo.

Sponsors