Article

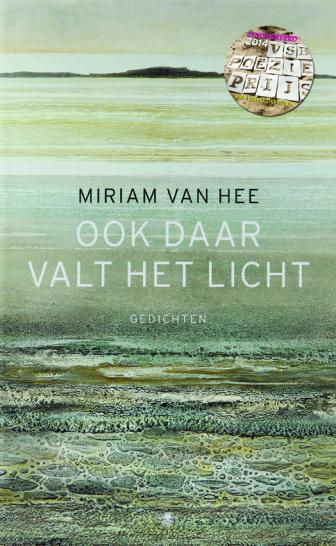

there too falls the light – Miriam Van hee (De Bezige Bij, 2013)

there too falls the light

November 18, 2013

at the rowing course, ghent

see how my father sets out on the water in a small boat

he rows with steady strokes and in between

is silence, he stirs the water with his oars

making waves that reach the banks later

there where I’ve left already, I’m cycling along the waterside

I call out that his speed is seven and a half knots per hour

he’s got his back to my view, he sees

where we were, I see what’s ahead, he’s wearing

a kyrgyz hat, not a real one but something made of

faded cotton, for the wind is too strong, he says

too strong for a hat, and on his feet he’s wearing

galoshes that belonged to his father-in-law

they stay in place, he says, in case he ends up

in the deep-end after all, he loved the water, the way he

loved my mother for in the middle of the sea

she was the only thing missing, he let slip

one day, and what about us, I thought and waved

goodbye, he couldn’t wave back, I called

but he couldn’t hear me, he was rowing and it looked

so effortless for him, slowly he fulfilled

his earthly duties while looking at me, on the shore,

now and then, he was moved, perhaps, but from here

I couldn’t tell, it may just as well have been

a game whose rules I didn’t know

and I thought I could leave him there, the water

understood him and carried him back to front

back to the shore

Miriam Van hee

from ook hier valt het licht

(translation by Judith Wilkinson)

Miriam Van hee made her debut in 1978 with the collection Het karige maal (‘The frugal meal’), that was awarded the West-Flemish Literary Prize. In that same year she began working on the promotion of international poetry in her capacity as initiator and editor of the poetry series for the Masereel Foundation. In that connection she translated various works, including the poetry of Anna Akhmatova. By then she was in her late twenties, had made a number of trips to the Soviet Union and had completed her Slavonic studies. Since the late nineteen-eighties she has been lecturing in Russian Literature and Grammar at the University of Antwerp.

What is especially appreciated in the work of Van hee is her careful composition and extremely good command of language which enables her to express the minutest of nuances. Miriam Van hee is no poet of sweeping generalizations, no messenger or great theorist. Her poetry has to do with the exploring of everyday reality, with carefully feeling her way, with touching on and observing situations which, though they may seem rather ordinary and mundane, are actually very specifically experienced. She uses no capitals or full stops preferring to allow the words and lines to speak for themselves. In that way, she is able to create a distance between the narrator and what is told, between the location described and the position of the ever-present ‘I’.

The passage of time is a recurrent theme in the work of Van hee, just as is travelling, and moving through time and space. Despite the choice of commonplace subjects, this emerges from the direct allusions to death and life, but also from the ways in which time – which varies for everyone depending on the situations and places people find themselves in – is experienced. References to the past might be viewed as pure nostalgia, but they serve to reflect upon the present. Much the same might be said of the threats that may be read into references to the future. Everything serves to underscore the here and now of the poem in question.

The fact that the future is not something one should passively allow to befall one is also clearly apparent from Van hee’s attitude towards being a poet. For her writing is a kind of necessity, an obligation, what in French is termed ‘Gagner sa vie’. She remarks that one is a poet for life though one should evolve: ‘Roughly speaking one develops more distance, one becomes more guarded. Occasionally my earlier poems got stranded in the anecdotal or merely imparted a certain atmosphere. Nowadays they do, I maintain, possess more ‘’content’’.’

Obviously, because of her travels, foreign countries feature prominently in the poetry of Miriam Van hee but because of that the familiarity and ordinariness of homeland comes to be viewed in a new light as it is seen from a different perspective. She appreciates the recognition received through her first foreign prize, the Jan Campert Prize, for the collection Winterhard (‘Winter-hardy’). Again 2007 proved to be a special year when the London Poetry Society made special mention of an anthology of English translations of her work and the collection Buitenland (‘Abroad’) came out. That collection saw no less than five reprints and it was awarded the Herman de Coninck Prize – both by the professional jury and the general public. What the jury particularly praised was the way in which everyday reality was sketched in a contemplative and slightly melancholic tone without becoming sombre.

Van hee strikes a balance between finding involvement in the world and reflecting individual loss, between having an eye for major historical events and making intimate observations. With tremendous precision and nuance she is able to conjure up both the abominations of Eastern Europe and the landscapes and personages of her own youth. All the while she questions, in the subtlest of ways, just how she can relate to that. This poet is an arrow of fire: she sets nothing alight but reminds us that light does exist.

at the rowing course, ghent

see how my father sets out on the water in a small boat

he rows with steady strokes and in between

is silence, he stirs the water with his oars

making waves that reach the banks later

there where I’ve left already, I’m cycling along the waterside

I call out that his speed is seven and a half knots per hour

he’s got his back to my view, he sees

where we were, I see what’s ahead, he’s wearing

a kyrgyz hat, not a real one but something made of

faded cotton, for the wind is too strong, he says

too strong for a hat, and on his feet he’s wearing

galoshes that belonged to his father-in-law

they stay in place, he says, in case he ends up

in the deep-end after all, he loved the water, the way he

loved my mother for in the middle of the sea

she was the only thing missing, he let slip

one day, and what about us, I thought and waved

goodbye, he couldn’t wave back, I called

but he couldn’t hear me, he was rowing and it looked

so effortless for him, slowly he fulfilled

his earthly duties while looking at me, on the shore,

now and then, he was moved, perhaps, but from here

I couldn’t tell, it may just as well have been

a game whose rules I didn’t know

and I thought I could leave him there, the water

understood him and carried him back to front

back to the shore

Miriam Van hee

from ook hier valt het licht

(translation by Judith Wilkinson)

What is especially appreciated in the work of Van hee is her careful composition and extremely good command of language which enables her to express the minutest of nuances. Miriam Van hee is no poet of sweeping generalizations, no messenger or great theorist. Her poetry has to do with the exploring of everyday reality, with carefully feeling her way, with touching on and observing situations which, though they may seem rather ordinary and mundane, are actually very specifically experienced. She uses no capitals or full stops preferring to allow the words and lines to speak for themselves. In that way, she is able to create a distance between the narrator and what is told, between the location described and the position of the ever-present ‘I’.

The passage of time is a recurrent theme in the work of Van hee, just as is travelling, and moving through time and space. Despite the choice of commonplace subjects, this emerges from the direct allusions to death and life, but also from the ways in which time – which varies for everyone depending on the situations and places people find themselves in – is experienced. References to the past might be viewed as pure nostalgia, but they serve to reflect upon the present. Much the same might be said of the threats that may be read into references to the future. Everything serves to underscore the here and now of the poem in question.

The fact that the future is not something one should passively allow to befall one is also clearly apparent from Van hee’s attitude towards being a poet. For her writing is a kind of necessity, an obligation, what in French is termed ‘Gagner sa vie’. She remarks that one is a poet for life though one should evolve: ‘Roughly speaking one develops more distance, one becomes more guarded. Occasionally my earlier poems got stranded in the anecdotal or merely imparted a certain atmosphere. Nowadays they do, I maintain, possess more ‘’content’’.’

Obviously, because of her travels, foreign countries feature prominently in the poetry of Miriam Van hee but because of that the familiarity and ordinariness of homeland comes to be viewed in a new light as it is seen from a different perspective. She appreciates the recognition received through her first foreign prize, the Jan Campert Prize, for the collection Winterhard (‘Winter-hardy’). Again 2007 proved to be a special year when the London Poetry Society made special mention of an anthology of English translations of her work and the collection Buitenland (‘Abroad’) came out. That collection saw no less than five reprints and it was awarded the Herman de Coninck Prize – both by the professional jury and the general public. What the jury particularly praised was the way in which everyday reality was sketched in a contemplative and slightly melancholic tone without becoming sombre.

Translator: Diane Butterman

Source: from the jury report upon nomination

Sponsors