Article

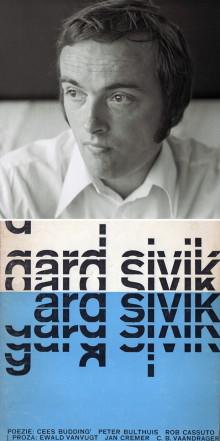

Wim Brands interviews Hans Sleutelaar

Not fiction but reality

June 04, 2015

Sleutelaar lives in Rotterdam again, ever since his wife fell ill and they were forced to leave Thailand. Since she passed away, he has been living in that apartment, just outside the city centre, on historical ground, as he himself phrases it: ‘I am from this neighbourhood, and Gard Sivik’s editorial office was located not far from here’.

He points at the bare earth next to the tracks. ‘Imagine how beautiful and lusciously green that will be when, soon, spring will truly come.’ And I think of the poem he wrote on the bombardment of Rotterdam, the end of it:

Our conversation is interrupted by a kitchen timer. ‘It goes off every half hour’, says Sleutelaar. ‘I have Parkinson’s, and I need regular physical exercise. Meanwhile, I could never have dreamed becoming this old, nearly eighty. And you have to die of something, so how can I complain’.

While he tells me that he is a lucky man, all things considered, I think of the poem he wrote about his grandmother.

I read it to him. ‘That’s how a poem should be for me’, says Sleutelaar. ‘Angular and simplistic. Pithy, and commonly legitimate. Trust me, writing a lot, then, becomes difficult. Besides, I have always found life to be time-consuming.’

Poems chanced upon him. Wherewith it should be noted that chance is nothing but what you make of it, what is your due, after patiently keeping silent. ‘I remember being banned from driving, and going to Norway by moped because of it. It was in that country, that that poem about my father announced itself, about a boy, me, seeing a dead person for the first time, and a friend for the last time, but also a man who would have been a father, but wasn’t, a father whose gaunt face betrayed resentment and grief. That whole life of his, our complicated relationship, with all its contradictions, passed before me in complete clarity in that poem’.

Our conversation arrives at C. B. Vaandrager, his childhood friend who became increasingly unmanageable as the years progressed, until the point at which Sleutelaar found out that that childhood friend was planning to kill him: ‘Cor totally lost it. The remarkable thing is that, in 1955 already, I wrote a poem that attempted to describe his fate. In hindsight, you might call it visionary’.

I ask him whether he still reads a lot of poetry. Little time, says Sleutelaar. ‘I go to the gym to do exercises nearly every day. Evening comes before you know it’. He points at a copy of The New York Review of Books, lying on the bed. ‘I think I might cancel my subscription, I barely get around to it.’

He ascertains it matter-of-factly, similar to the way in which he reacts to my surprise at the scant amount of books in his bookcase. ‘My possessions are still in Thailand, being taken care of by my son who lives there. My bookcase contains what interests me at the moment’ .

The writings of Confucius, Lao-tse, and the collected works of Ida Gerhardt. ‘When you’re young, you’re so unbelievably haughty. We thought we were just going to reinvent poetry. As you become older, you find out that you are part of a long tradition. Ida Gerhardt is also a benchmark in this tradition of mine. That angularity of hers, by the way, is so Rotterdammish as well’.

Sleutelaar hopes the Dutch publishing house De Bezige Bij will publish his collected poems this summer. He shows me the typescript, the epigraph is by Martial: ‘You cannot be harsher to my puny verses, than I myself have been’.

He dedicates the book to his deceased wife, Kristien. He wants to write a poem about her. It’s there, he knows, he awaits.

‘I carry around what it was like, those last moments with her. I had no words. I lifted her, and held her’.

{event id="186" title="Not fiction but reality"}. Wednesday, 10 June, 2015, 20:00-21:30. An evening on Gard Sivik and Barbarber with, amongst others, Hans Sleutelaar, Erik Brus and Bertram Mourits. Host: Wim Brands.

‘Not fiction, but reality should be declared art’ was the Zestigers’ (Dutch poets in the 1960s) motto. In light of the special program in their honor for the 46th Poetry International Festival – held on 10 June, 20:00, at the Rotterdam Schouwburg – poet and announcer Wim Brands visits Hans Sleutelaar, who formed the editorial staff of the journal Gard Sivik alongside Armando, Hans Verhagen and C.B. Vaandrager.

After my visit, waiting for the bus, I’m addressed by a friend of Sleutelaar’s on his morning walk. ‘Have you seen the way he lives? Tiny. Kitchenette, table, bed, a few books. Like a monk. Sometimes I think the man is actually a Buddhist.’Sleutelaar lives in Rotterdam again, ever since his wife fell ill and they were forced to leave Thailand. Since she passed away, he has been living in that apartment, just outside the city centre, on historical ground, as he himself phrases it: ‘I am from this neighbourhood, and Gard Sivik’s editorial office was located not far from here’.

He points at the bare earth next to the tracks. ‘Imagine how beautiful and lusciously green that will be when, soon, spring will truly come.’ And I think of the poem he wrote on the bombardment of Rotterdam, the end of it:

The sky above the city is torch red

The people staring at the glow

The puddle ripple-free, empty

In the moonlight, we walk home

It is a gentle night

The Jericholaan is blossoming

The people staring at the glow

The puddle ripple-free, empty

In the moonlight, we walk home

It is a gentle night

The Jericholaan is blossoming

(trans. by Jonas van de Poel)

Our conversation is interrupted by a kitchen timer. ‘It goes off every half hour’, says Sleutelaar. ‘I have Parkinson’s, and I need regular physical exercise. Meanwhile, I could never have dreamed becoming this old, nearly eighty. And you have to die of something, so how can I complain’.

While he tells me that he is a lucky man, all things considered, I think of the poem he wrote about his grandmother.

She grew old and died

which just a few are granted,

fearless, without complaint.

Sometimes, at an uncertain hour

for a moment she appears.

which just a few are granted,

fearless, without complaint.

Sometimes, at an uncertain hour

for a moment she appears.

(trans. by Jonas van de Poel)

I read it to him. ‘That’s how a poem should be for me’, says Sleutelaar. ‘Angular and simplistic. Pithy, and commonly legitimate. Trust me, writing a lot, then, becomes difficult. Besides, I have always found life to be time-consuming.’

Poems chanced upon him. Wherewith it should be noted that chance is nothing but what you make of it, what is your due, after patiently keeping silent. ‘I remember being banned from driving, and going to Norway by moped because of it. It was in that country, that that poem about my father announced itself, about a boy, me, seeing a dead person for the first time, and a friend for the last time, but also a man who would have been a father, but wasn’t, a father whose gaunt face betrayed resentment and grief. That whole life of his, our complicated relationship, with all its contradictions, passed before me in complete clarity in that poem’.

Our conversation arrives at C. B. Vaandrager, his childhood friend who became increasingly unmanageable as the years progressed, until the point at which Sleutelaar found out that that childhood friend was planning to kill him: ‘Cor totally lost it. The remarkable thing is that, in 1955 already, I wrote a poem that attempted to describe his fate. In hindsight, you might call it visionary’.

you are in a state of outbreak

like a bird

at daybreak, before his song begins

like a bird

at daybreak, before his song begins

(trans. by Jonas van de Poel)

I ask him whether he still reads a lot of poetry. Little time, says Sleutelaar. ‘I go to the gym to do exercises nearly every day. Evening comes before you know it’. He points at a copy of The New York Review of Books, lying on the bed. ‘I think I might cancel my subscription, I barely get around to it.’

He ascertains it matter-of-factly, similar to the way in which he reacts to my surprise at the scant amount of books in his bookcase. ‘My possessions are still in Thailand, being taken care of by my son who lives there. My bookcase contains what interests me at the moment’ .

The writings of Confucius, Lao-tse, and the collected works of Ida Gerhardt. ‘When you’re young, you’re so unbelievably haughty. We thought we were just going to reinvent poetry. As you become older, you find out that you are part of a long tradition. Ida Gerhardt is also a benchmark in this tradition of mine. That angularity of hers, by the way, is so Rotterdammish as well’.

Sleutelaar hopes the Dutch publishing house De Bezige Bij will publish his collected poems this summer. He shows me the typescript, the epigraph is by Martial: ‘You cannot be harsher to my puny verses, than I myself have been’.

He dedicates the book to his deceased wife, Kristien. He wants to write a poem about her. It’s there, he knows, he awaits.

‘I carry around what it was like, those last moments with her. I had no words. I lifted her, and held her’.

{event id="186" title="Not fiction but reality"}. Wednesday, 10 June, 2015, 20:00-21:30. An evening on Gard Sivik and Barbarber with, amongst others, Hans Sleutelaar, Erik Brus and Bertram Mourits. Host: Wim Brands.

© Wim Brands

Translator: Jonas van de Poel

Source: VPRO Gids Bijlage - Poetry International Festival 2015

Sponsors

Partners

LantarenVenster – Verhalenhuis Belvédère