Article

Dimiter Kenarov on poetry and conflict in Ukraine

The Mushrooms of Donbas

January 20, 2015

It may be that Ukrainian-language literature, traditionally scorned as peasant and inferior to the beauties and grandeur of its Russian cousin, represents the most authentic essence of Ukraine. In spite of some Russian nationalist claims that Ukraine ‘is not even a real country’, or that Ukraine is simply the ‘Little Russia’ of yore, Ukraine has its particular, highly individual spirit, and contemporary Ukrainian poetry stands a testimony to that. There is very little of the Russian literary tradition in the five poems I’ve selected here from Poetry International’s archive. With their narrative, free-verse forms, and chatty, casual tone, these poems are somewhat closer to American and Polish models than Russian syllabotonic ones.

The question of Ukrainian literary and national identity is the direct subject of Andriy Bondar’s ironic poem ‘The Roman Alphabet’. Using Roman letters, instead of the usual Cyrillic ones, it pokes gentle fun at Ukrainians oriented to the West, who believe that switching to the Roman alphabet would make Ukrainian poetry more accessible, ‘our people will steal less’, and ‘“voila!” – we are part of europe’. To read Bondar’s poem, written in 2002, in 2015 is to realize how uncannily relevant it is to the current debates surrounding the Ukrainian conflict, especially in such lines as ‘in order for ukraine to survive between east and west / it must shrink to digestible dimensions / that is to the 6 regions west of the river zbruch’.

In fact, although all of the poems featured here were written years ago and the poets could not have possibly foreseen – no one in Ukraine did – that in 2014 their country would be thrown into war with Russia, they carry a certain prophetic spirit and quite surprisingly, in the old Romantic tradition, turn their unsuspecting authors into oracles, Shelley’s ‘unacknowledged legislators of the world’.

Yuri Andrukhovych’s poem ‘Without You’, for example, is ostensibly about the absent beloved, but the mention of ‘A few armed conflicts, / a couple of traitors on TV’ immediately place it in a painfully familiar environment and turn the author’s intentions around: the armed conflicts, which in the poem originally function as images of distance and abstraction (in opposition to the intimate space of the lovers), today are happening within Ukraine itself. The world of the lovers and world of war have now, unfortunately, become one and the same.

‘Prisoner’ by Natalka Bilotserkivets and ‘Clytemnestra’ by Oksana Zabuzhko, two more love poems of dark vision, are also transformed in unexpected ways by today’s context, and thus attain new depths and levels of reading. What was initially aimed to be just a literary metaphor or a mythical character functioning as metaphor is now bizarrely transformed into fact, into metonymy. Both Zabrusko’s Agamemnon, ‘clanging with brass / Like a war-bloated idol’ and making violent love to the speaker, and Bilotserkivets’s prisoner, ‘waving a white flag’, could be real characters right out of the conflict in eastern Ukraine. This is, admittedly, a rather literal reading, but it points to the ways historical context can radically alter our ways of viewing a work of art.

Finally, Serhiy Zhadan’s poem ‘The Mushrooms of Donbas’ sounds so contemporary that it could have been written just yesterday. It tells the story of a worker at a former mining pumping station in Donbas (the coal-rich region in eastern Ukraine, which is now the center of armed hostilities), who starts to grow psychedelic mushrooms after the collapse of the Ukrainian economy post-1991. A local gang (Donbas was and still is notorious for its criminal networks) wants to take the protagonist's new business away, but he fights back, because ‘There are just things you have to answer for, things / you can’t just let go’. This little mushroom enterprise, this little ‘island of freedom’, becomes the true homeland: not some theoretical nationalist idea of a country or an imagined community, but a specific plot of land that one owns and works daily. It is, to paraphrase John Locke, property that becomes private through one’s own investment of labor into it. And this property, this personal plot of land, is the only land worth fighting for.

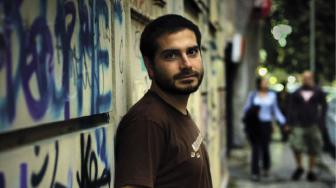

In a strange case of life imitating art, the author of the poem, Zhadan, Ukraine's star poet, was severely beaten last year for standing his ground against pro-Russian separatists in his hometown of Kharkiv. He suffered cuts to the head, a split eyebrow, and a concussion.

Dimiter Kenarov is a poet and freelance journalist based in Sofia, Bulgaria. His English-language work has appeared in Esquire, Outside, The Nation, The Atlantic, Foreign Policy, The International New York Times and The Virginia Quarterly Review, among many others. He is also the author of two collections of Bulgarian poetry. Twitter: @dkenarov

About a year ago, Ukraine – and Europe – changed dramatically. What was initially a peaceful protest in Kiev against corruption and nepotism suddenly turned violent. The police used lethal force against protestors, killing about 100 people. Facing a full-blown revolution, the president Viktor Yanukovych fled the country, and a new government took power.

But this was only the opening act of what proved to be a much bloodier scenario. In late February 2014, masked Russian troops invaded the Crimean peninsula and hastily organized a referendum, resulting in Crimea’s annexation by Russia. In the meantime, civil unrest and violence in the east of Ukraine threw the country in its worst crisis since World War II. The regions of Donetsk and Luhansk turned into battlefields, where the Ukrainian military fought pro-Russian separatists. The conflict, which is still ongoing, has so far claimed over 5,000 lives, including 298 people on board Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, which was downed by a surface-to-air missile in the Donetsk region last July.

Ukraine has had a complex political and cultural history, often split between its close Slavic ties to Russia and its European spirit. For centuries the region was part of the Russian Empire, and then the Soviet Union, becoming independent only in 1991. It is often hard to draw a clear line between Ukrainian and Russian ethnicity, as many people are intermarried or children of intermarriages. Language is an important construct of identity, but, except in the easternmost and westernmost parts of the country, most Ukrainians are bilingual, speaking both Russian and Ukrainian, further complicating the issue.It may be that Ukrainian-language literature, traditionally scorned as peasant and inferior to the beauties and grandeur of its Russian cousin, represents the most authentic essence of Ukraine. In spite of some Russian nationalist claims that Ukraine ‘is not even a real country’, or that Ukraine is simply the ‘Little Russia’ of yore, Ukraine has its particular, highly individual spirit, and contemporary Ukrainian poetry stands a testimony to that. There is very little of the Russian literary tradition in the five poems I’ve selected here from Poetry International’s archive. With their narrative, free-verse forms, and chatty, casual tone, these poems are somewhat closer to American and Polish models than Russian syllabotonic ones.

The question of Ukrainian literary and national identity is the direct subject of Andriy Bondar’s ironic poem ‘The Roman Alphabet’. Using Roman letters, instead of the usual Cyrillic ones, it pokes gentle fun at Ukrainians oriented to the West, who believe that switching to the Roman alphabet would make Ukrainian poetry more accessible, ‘our people will steal less’, and ‘“voila!” – we are part of europe’. To read Bondar’s poem, written in 2002, in 2015 is to realize how uncannily relevant it is to the current debates surrounding the Ukrainian conflict, especially in such lines as ‘in order for ukraine to survive between east and west / it must shrink to digestible dimensions / that is to the 6 regions west of the river zbruch’.

In fact, although all of the poems featured here were written years ago and the poets could not have possibly foreseen – no one in Ukraine did – that in 2014 their country would be thrown into war with Russia, they carry a certain prophetic spirit and quite surprisingly, in the old Romantic tradition, turn their unsuspecting authors into oracles, Shelley’s ‘unacknowledged legislators of the world’.

Yuri Andrukhovych’s poem ‘Without You’, for example, is ostensibly about the absent beloved, but the mention of ‘A few armed conflicts, / a couple of traitors on TV’ immediately place it in a painfully familiar environment and turn the author’s intentions around: the armed conflicts, which in the poem originally function as images of distance and abstraction (in opposition to the intimate space of the lovers), today are happening within Ukraine itself. The world of the lovers and world of war have now, unfortunately, become one and the same.

‘Prisoner’ by Natalka Bilotserkivets and ‘Clytemnestra’ by Oksana Zabuzhko, two more love poems of dark vision, are also transformed in unexpected ways by today’s context, and thus attain new depths and levels of reading. What was initially aimed to be just a literary metaphor or a mythical character functioning as metaphor is now bizarrely transformed into fact, into metonymy. Both Zabrusko’s Agamemnon, ‘clanging with brass / Like a war-bloated idol’ and making violent love to the speaker, and Bilotserkivets’s prisoner, ‘waving a white flag’, could be real characters right out of the conflict in eastern Ukraine. This is, admittedly, a rather literal reading, but it points to the ways historical context can radically alter our ways of viewing a work of art.

Finally, Serhiy Zhadan’s poem ‘The Mushrooms of Donbas’ sounds so contemporary that it could have been written just yesterday. It tells the story of a worker at a former mining pumping station in Donbas (the coal-rich region in eastern Ukraine, which is now the center of armed hostilities), who starts to grow psychedelic mushrooms after the collapse of the Ukrainian economy post-1991. A local gang (Donbas was and still is notorious for its criminal networks) wants to take the protagonist's new business away, but he fights back, because ‘There are just things you have to answer for, things / you can’t just let go’. This little mushroom enterprise, this little ‘island of freedom’, becomes the true homeland: not some theoretical nationalist idea of a country or an imagined community, but a specific plot of land that one owns and works daily. It is, to paraphrase John Locke, property that becomes private through one’s own investment of labor into it. And this property, this personal plot of land, is the only land worth fighting for.

Everything that you make with your hands, works for you.

Everything that reaches your conscience beats

in rhythm with your heart.

We stayed on this land, so that it wouldn’t be far

for our children to visit our graves.

This is our island of freedom

our expanded

village consciousness.

Penicillin and Kalashnikovs – two symbols of struggle,

the Castro of Donbas leads the partisans

through the fog-covered mushroom plantations

to the Azov Sea.

Everything that reaches your conscience beats

in rhythm with your heart.

We stayed on this land, so that it wouldn’t be far

for our children to visit our graves.

This is our island of freedom

our expanded

village consciousness.

Penicillin and Kalashnikovs – two symbols of struggle,

the Castro of Donbas leads the partisans

through the fog-covered mushroom plantations

to the Azov Sea.

In a strange case of life imitating art, the author of the poem, Zhadan, Ukraine's star poet, was severely beaten last year for standing his ground against pro-Russian separatists in his hometown of Kharkiv. He suffered cuts to the head, a split eyebrow, and a concussion.

Dimiter Kenarov is a poet and freelance journalist based in Sofia, Bulgaria. His English-language work has appeared in Esquire, Outside, The Nation, The Atlantic, Foreign Policy, The International New York Times and The Virginia Quarterly Review, among many others. He is also the author of two collections of Bulgarian poetry. Twitter: @dkenarov

© Dimiter Kenarov

Sponsors

Partners

LantarenVenster – Verhalenhuis Belvédère