Article

Reflections on Seamus Heaney

The Tollund Man and me

June 27, 2014

Had it not been for Seamus Heaney, I would never have gone to Silkeborg in Jutland to see the Tollund Man, and I would never have written a poem with the same title as the one made famous by Heaney, but I will tell things in the order in which they happened. The first time I got acquainted with the poetry of Seamus Heaney was through a friend, in the late Eighties. I studied German and English Literature in Cologne, and this friend, Stephan, wrote his thesis about “North” and some of Heaney’s other poems concerned with peat and bog and pre-historical things in Northern Europe. While I had missed the chance to go abroad during my student years, Stephan had spent one term in Dublin, he also did Scandinavian Studies and Anglo-American History, he learnt Norwegian and given the fact that the City of Dublin was founded by the Vikings, Heaney’s poems were an obvious and rewarding choice for his thesis. He asked me to read it, and this is how I got to know ‘The Tollund Man’ and ‘The Grauballe Man’, learned about ‘Mossbawn’, ‘Funeral Rites’ and ‘Viking-Dublin’.

But, though I read Stephan’s paper carefully and with great interest, I retained a certain distance, and it did not make me a Heaney-reader right away. I think there were two reasons for this. First, the poems didn’t meet with my own writing. I had started in a rather personal manner, not concerned with taking sides, but then I got involved in aesthetic debate, and by 1989, I was more into the experimental side of things, Ernst Jandl and Thomas Kling being the poets who excited me most. My own thesis was about Friederike Mayröcker’s prose. I probably held Heaney to be too modest, too realistic, or whatever. Second reason was that Stephan and I had a way of having different opinions on almost every field of interest, and since he was very critical about Mayröcker, I had to say something against his favorites as well.

But I kept these poems in the back of my mind, especially ‘The Tollund Man’ – the dead man from the Iron Age found in the moors of Jutland to be discovered by peat-cutters and then to be revived in a poem by Seamus Heaney – had slowly but certainly begun to work on my imagination. From childhood days, I had a romantic interest in moors, there was a region in the East of Belgium called ‘Das Hohe Venn’ or ‘Haute-Fagne’ where we used to walk along planked paths through a vast and lonely land that always impressed me. I used to go there with my father in wintertime, there was snow all over the peat and the planks, and there was a van selling Belgian fries with a thick delicious mayonnaise I could not forget. And there were crosses marking places where people had sunk into the fen and died, especially one called La Croix de Fiancés stuck in my memory, but lonely landscapes and childhood images were not the prime stuff that my poems were made of, by that time.

In the spring of 1995, I went to Ireland to take part in a festival in Listowel, County Kerry, and on this occasion I bought Seamus Heaney’s recent book of poems, Seeing Things. Reading in this volume brought me a strange kind of joy that is difficult to describe. My own writing had begun to undergo a change, and now I was much more open-minded towards Heaney’s ways of dealing with history great and small, with traditions from Dante to Larkin and Hughes, and his autobiography. There are verses in this volume that really struck me at once, like the three-line-poem written on New Year’s Day of 1987: “Dangerous pavements. / But I face the ice this year / With my father’s stick”. These lines keep making me happy every time I read them, because they express an emotional attitude in a reluctant, clear-headed and most economical way, relying on the little word ‘but’ to tell a whole story. Just skipping through and turning the pages in Seeing Things also produced a kind of happiness, because the clear architecture of the three-line-stanzas appealed to me, and wherever I chanced to read, the poems gave the impression of a poet knowing his ways and writing only what is necessary.

I was glad to see him awarded the Noble Prize later that same year, certainly the best decision in decades. Having become a Heaney reader in my mid-thirties seemed the right time for me, and now I could see there were a few things we might have in common. One of my earliest poems, from my pre-experimental beginnings, now strangely reminded me of Heaney’s famous “Digging” poem, in which he declares to dig with a pen rather than a spade, as his father and grandfather had done. My poem ‘brotlose kunst’ (‘breadless art’) was about planting bushes, peeling potatoes and patching air tubes, and contrasted these decent activities with the rather indecent activity of writing. Although I did not grow up as a farmer’s son, working with one’s hands was rather more accepted in my family than fiddling with words, and I have always felt that being a poet was not in the usual run of things. Some of the energy you need to hold on to the poetic voice is drawn from a wish to convince your elders, dead as they may be, that writing poetry is not a waste of time nevertheless.

Reading Heaney more closely, though, I had to discover he was a poet with many difficult words for a reader from a foreign language. I don’t know if his vocabulary is held to be very large by English readers, but I think it contains many words that you don’t usually get in touch with when you’re not a native English speaker. Specific words, often concerned with manual work, from peat-cutters and field-workers to blacksmiths and certain traditional crafts he had taken a fancy for, by this way expressing his love for all the works of hand he estimated but could not do himself, I guess.

Of course you can look these words up in dictionaries, but I don’t love to do that when I read poetry. I like to rely on sound and I firmly believe in what Eliot said about his experience with reading Dante in the original: that genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood. So many of Heaney’s poems retained their certain dim areas of understanding due to my imperfect knowledge of English, this made the poems but all the more attractive to me. Inexhaustible sources of sound and image, models of poetry that I can turn to when I am in low spirits, waiting for the next poem to come – looking into Heaney is always a way of reassuring yourself that poetry is possible.

There is another class of strange words in Heaney’s poems that were unfamiliar but at the same time had an immediate spell, by which I mean place names. Heaney himself writes, in ‘The Tollund Man’, of the fascination of “Saying the names / Tollund, Grauballe, Nebelgard”, and in ‘Toome’ he describes how the movement of the tongue in the mouth while pronouncing the name of this village in County Antrim produces the sensation of being there, not only now, but in pre-historical times:

till I am sleeved in / alluvial mud that shelves / suddenly under / bog water and tributaries, / and elvers tail my hair.

To place the names of disregarded, forgotten, or only locally known places in your poetry, names that are full of resonance for you but at first only a pattern of vocals and consonants to your reader, is a poetic trick or device, I am sure, will work in every language. It will offer the reader a wealth of association only because he or she knows such names, different names, himself or herself and shares your joy in saying them. They hold a promise, and the promise is you can really comprise what you wish to preserve of the world in your poem. I like to say the names Holzheim, Grefrath, Mermuth, or Kossenblatt in my poetry just as much as I like to read the names Anahorish, Toome, Höfn, or Glanmore in Heaney’s or Burnt Norton, East Coker, and Little Gidding in Eliot’s poetry. As far as Eliot is concerned, I really went to all the places, while I did my translation of ‘The Four Quartets’, and it was a little bit like meeting Mr. Eliot.

I had no opportunity to meet Mr. Heaney in person, but I chanced to come across some of the places he has named in his poems while I stayed in Ireland for two months during the summer of 2005. I lived in Dublin and I went to Belfast, I went to Glendalough in the Wicklow Mountains and walked where St. Kevin had his retreat, a cell on the lake where he held out his arm so that the blackbird could build his nest in the saint’s hand, so that Heaney could tell us in his beautiful poem from The Spirit Level. I also saw the great chambers at Boyne that are named in ‘Funeral Rites’, and seeing this enormous site of megalithic culture went into the making of my poem ‘untergrund’, which explores the things men do under earth from “preparing a sepulchre” to the building of huge underground systems for the tube. In my early twenties I had spent my holidays in Clapham Common in London SW4, travelling on the Northern Line every day and reading Thomas Mann’s Der Zauberberg while I did so. During my stay in Dublin, the attacks on the London Underground came quite as a shock, and this also went into the making of my ‘untergrund’ poem, saying the names: “oval, clapham, edgware road” in order to make these places still accessible to me, whatever might happen.

A year later, in June 2006, I happened to be where we are right now, in Rotterdam. There was a reading at the Goethe Institute, presenting an anthology of Dutch and Flemish poetry in German translation, two weeks after Poetry International. There were still posters of the festival all over the place, so I found out I had missed the chance to see Seamus Heaney, and I felt a little bit sad. On my way home I went into the Waterstone’s bookshop in Amsterdam, and there I got myself his new book that made me happy alone by its title, District and Circle, immortalizing another Line of the London Underground, and again I felt some sort of hidden bond between us. There is one poem in this volume that has become my all-time Heaney favorite, it is the last poem of the collection and I would like to read it to you in full.

THE BLACKBIRD OF GLANMORE

On the grass when I arrive,

Filling the stillness with life,

But ready to scare off

At the very first wrong move.

In the ivy when I leave.

It’s you, blackbird, I love.

I park, pause, take heed.

Breathe. Just breathe and sit

And lines I once translated

Come back: ‘I want away

To the house of death, to my father

Und the low clay roof.’

And I think of one gone to him,

A little stillness dancer –

Haunter-son, lost brother –

Cavorting through the yard,

So glad to see me home,

My homesick first term over.

And think of a neighbour’s words

Long after the accident:

‘Yon bird on the shed roof,

Up on the ridge for weeks –

I said nothing at the time

But I never liked yon bird.’

The automatic lock

Clunks shut, the blackbird’s panic

Is shortlived, for a second

I’ve a bird’s eye view of myself,

A shadow on raked gravel

In front of my house of life.

Hedge-hop, I am absolute

For you, your ready talkback,

Your each stand-offish comeback,

Your picky, nervy goldbeak –

On the grass when I arrive,

In the ivy when I leave.

I don’t know how you feel about it, but I think this is utterly beautiful. I love what Heaney does with the sounds, half-rhymes and alliterations, and his own sort of sprung rhythm, not so much inspired by Hopkins, maybe, but rather by the blackbird’s movements that are captured here in an unforgettable way. I am sure that this poem will shine on for a long time; and you don’t need to know about the personal tragedies of the Heaney family, the death of one of Seamus’ younger brothers that is also alluded to in the poem ‘Mid-Term Break’ in Death of a Naturalist from 1966, and you don’t necessarily have to know that Glanmore is the place in County Wicklow where Heaney and his wife lived for some time in the Seventies. But everybody knows the meaning of a death-wish, everybody’s got a father and almost everybody may have seen a blackbird and watched it, and, to say it with Keats, “That is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know” to be touched by this poem.

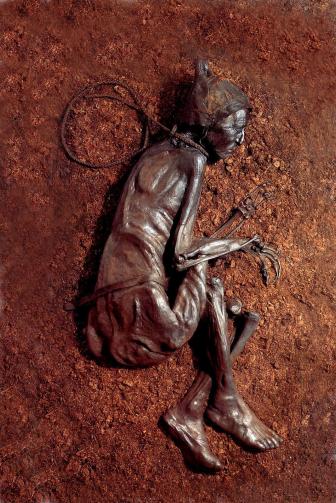

I fear that time is running out, and I would like to close with my own poem ‘der tollund-mann’ that was written in late 2011, a year and a half after I had seen the real man from the moors in Silkeborg, Jutland, together with my wife Nadja when we returned from a holiday in Norway. We stood there, really watching

and we also bought the catalogue I have here, containing the photographs that were Heaney’s inspiration because, unlike myself, he wrote the poem before seeing the man, but went to see him years later. I had not seen these photographs before seeing the man, but I knew the poem, and this was what made me stop in Jutland. There is one thing to tell, however, before I read the poem, because you may want to know what happened to Stephan. I am sad to say that he died, more than one year ago, and even sadder for me, that we totally fell out of contact years before this happened because of differences other than literary ones. There was no way to talk again, and I did not have the opportunity to tell him either about seeing the Tollund Man, about writing my poem, or about holding a Heaney lecture in Rotterdam. So the only thing left is to remember, and to tell, the driving forces for speech and poetry, wherever you go. As Heaney puts it: “Out there in Jutland / In the old man-killing parishes / I will feel lost, / Unhappy and at home.”

der tollund-mann

man hat ihn nicht im hohen venn gefunden, dem mir von

jugend an bekannten moor; oben in jütland kam der mann

mit dem vom moorwasser gefärbten kurzhaarschnitt samt

bartstoppeln u. augenbrauen aus diesem immer feuchten

grund hervor. torfstecher waren es die ihn fanden, 2 ½ m

unter der erde; torfstecher war er selber auch. der körper

nackt bis auf die lederhaube bis auf den ledergürtel um die

lenden bis auf die lederschlinge um den hals: opferbrauch

der eisenzeit. sie haben ihm noch aug u. mund verschlossen

wie um zu sagen: wir bleiben dir gut; nur daß du sterben

mußtest ging nicht anders. die götter fordern das. du bist

tribut. als wir vor ihm standen rührte er uns wie er dalag

friedvoll ernst ja lieb geradezu. so lange in dem warmen

schoß gelegen. ein nickerchen nach seiner letzten mahlzeit:

brei aus pflanzensamen, wie die pollenanalyse klar ergab.

im späten winter oder frühen frühjahr, am kalten himmel

leuchtet stern um stern .. ich träume manchmal von einem

schmalen steg durchs hohe venn, fängt an zu schneien u.

ich kann nicht sehen wie nahe schon die büschel wollgras

stehen muß immer in die weichen flocken gehen mit meinem

mageninhalt der mich frisch erwärmt .. denn an der straße

steht ein imbißwagen u. leuchtet durch den schnee von fern.

During the 45th Poetry International Festival in Rotterdam we held a special programme honouring the life and work of Irish poet Seamus Heaney. For this occasion festival poet Norbert Hummelt (Germany) delivered the following speech about the relationship between Heaney’s work and his own:

Some day I will go to Aarhus / To see his peat-brown head, / The mild pods of his eyelids, / His pointed skin-cap.

Had it not been for Seamus Heaney, I would never have gone to Silkeborg in Jutland to see the Tollund Man, and I would never have written a poem with the same title as the one made famous by Heaney, but I will tell things in the order in which they happened. The first time I got acquainted with the poetry of Seamus Heaney was through a friend, in the late Eighties. I studied German and English Literature in Cologne, and this friend, Stephan, wrote his thesis about “North” and some of Heaney’s other poems concerned with peat and bog and pre-historical things in Northern Europe. While I had missed the chance to go abroad during my student years, Stephan had spent one term in Dublin, he also did Scandinavian Studies and Anglo-American History, he learnt Norwegian and given the fact that the City of Dublin was founded by the Vikings, Heaney’s poems were an obvious and rewarding choice for his thesis. He asked me to read it, and this is how I got to know ‘The Tollund Man’ and ‘The Grauballe Man’, learned about ‘Mossbawn’, ‘Funeral Rites’ and ‘Viking-Dublin’.

But, though I read Stephan’s paper carefully and with great interest, I retained a certain distance, and it did not make me a Heaney-reader right away. I think there were two reasons for this. First, the poems didn’t meet with my own writing. I had started in a rather personal manner, not concerned with taking sides, but then I got involved in aesthetic debate, and by 1989, I was more into the experimental side of things, Ernst Jandl and Thomas Kling being the poets who excited me most. My own thesis was about Friederike Mayröcker’s prose. I probably held Heaney to be too modest, too realistic, or whatever. Second reason was that Stephan and I had a way of having different opinions on almost every field of interest, and since he was very critical about Mayröcker, I had to say something against his favorites as well.

But I kept these poems in the back of my mind, especially ‘The Tollund Man’ – the dead man from the Iron Age found in the moors of Jutland to be discovered by peat-cutters and then to be revived in a poem by Seamus Heaney – had slowly but certainly begun to work on my imagination. From childhood days, I had a romantic interest in moors, there was a region in the East of Belgium called ‘Das Hohe Venn’ or ‘Haute-Fagne’ where we used to walk along planked paths through a vast and lonely land that always impressed me. I used to go there with my father in wintertime, there was snow all over the peat and the planks, and there was a van selling Belgian fries with a thick delicious mayonnaise I could not forget. And there were crosses marking places where people had sunk into the fen and died, especially one called La Croix de Fiancés stuck in my memory, but lonely landscapes and childhood images were not the prime stuff that my poems were made of, by that time.

In the spring of 1995, I went to Ireland to take part in a festival in Listowel, County Kerry, and on this occasion I bought Seamus Heaney’s recent book of poems, Seeing Things. Reading in this volume brought me a strange kind of joy that is difficult to describe. My own writing had begun to undergo a change, and now I was much more open-minded towards Heaney’s ways of dealing with history great and small, with traditions from Dante to Larkin and Hughes, and his autobiography. There are verses in this volume that really struck me at once, like the three-line-poem written on New Year’s Day of 1987: “Dangerous pavements. / But I face the ice this year / With my father’s stick”. These lines keep making me happy every time I read them, because they express an emotional attitude in a reluctant, clear-headed and most economical way, relying on the little word ‘but’ to tell a whole story. Just skipping through and turning the pages in Seeing Things also produced a kind of happiness, because the clear architecture of the three-line-stanzas appealed to me, and wherever I chanced to read, the poems gave the impression of a poet knowing his ways and writing only what is necessary.

I was glad to see him awarded the Noble Prize later that same year, certainly the best decision in decades. Having become a Heaney reader in my mid-thirties seemed the right time for me, and now I could see there were a few things we might have in common. One of my earliest poems, from my pre-experimental beginnings, now strangely reminded me of Heaney’s famous “Digging” poem, in which he declares to dig with a pen rather than a spade, as his father and grandfather had done. My poem ‘brotlose kunst’ (‘breadless art’) was about planting bushes, peeling potatoes and patching air tubes, and contrasted these decent activities with the rather indecent activity of writing. Although I did not grow up as a farmer’s son, working with one’s hands was rather more accepted in my family than fiddling with words, and I have always felt that being a poet was not in the usual run of things. Some of the energy you need to hold on to the poetic voice is drawn from a wish to convince your elders, dead as they may be, that writing poetry is not a waste of time nevertheless.

Reading Heaney more closely, though, I had to discover he was a poet with many difficult words for a reader from a foreign language. I don’t know if his vocabulary is held to be very large by English readers, but I think it contains many words that you don’t usually get in touch with when you’re not a native English speaker. Specific words, often concerned with manual work, from peat-cutters and field-workers to blacksmiths and certain traditional crafts he had taken a fancy for, by this way expressing his love for all the works of hand he estimated but could not do himself, I guess.

Of course you can look these words up in dictionaries, but I don’t love to do that when I read poetry. I like to rely on sound and I firmly believe in what Eliot said about his experience with reading Dante in the original: that genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood. So many of Heaney’s poems retained their certain dim areas of understanding due to my imperfect knowledge of English, this made the poems but all the more attractive to me. Inexhaustible sources of sound and image, models of poetry that I can turn to when I am in low spirits, waiting for the next poem to come – looking into Heaney is always a way of reassuring yourself that poetry is possible.

There is another class of strange words in Heaney’s poems that were unfamiliar but at the same time had an immediate spell, by which I mean place names. Heaney himself writes, in ‘The Tollund Man’, of the fascination of “Saying the names / Tollund, Grauballe, Nebelgard”, and in ‘Toome’ he describes how the movement of the tongue in the mouth while pronouncing the name of this village in County Antrim produces the sensation of being there, not only now, but in pre-historical times:

till I am sleeved in / alluvial mud that shelves / suddenly under / bog water and tributaries, / and elvers tail my hair.

To place the names of disregarded, forgotten, or only locally known places in your poetry, names that are full of resonance for you but at first only a pattern of vocals and consonants to your reader, is a poetic trick or device, I am sure, will work in every language. It will offer the reader a wealth of association only because he or she knows such names, different names, himself or herself and shares your joy in saying them. They hold a promise, and the promise is you can really comprise what you wish to preserve of the world in your poem. I like to say the names Holzheim, Grefrath, Mermuth, or Kossenblatt in my poetry just as much as I like to read the names Anahorish, Toome, Höfn, or Glanmore in Heaney’s or Burnt Norton, East Coker, and Little Gidding in Eliot’s poetry. As far as Eliot is concerned, I really went to all the places, while I did my translation of ‘The Four Quartets’, and it was a little bit like meeting Mr. Eliot.

I had no opportunity to meet Mr. Heaney in person, but I chanced to come across some of the places he has named in his poems while I stayed in Ireland for two months during the summer of 2005. I lived in Dublin and I went to Belfast, I went to Glendalough in the Wicklow Mountains and walked where St. Kevin had his retreat, a cell on the lake where he held out his arm so that the blackbird could build his nest in the saint’s hand, so that Heaney could tell us in his beautiful poem from The Spirit Level. I also saw the great chambers at Boyne that are named in ‘Funeral Rites’, and seeing this enormous site of megalithic culture went into the making of my poem ‘untergrund’, which explores the things men do under earth from “preparing a sepulchre” to the building of huge underground systems for the tube. In my early twenties I had spent my holidays in Clapham Common in London SW4, travelling on the Northern Line every day and reading Thomas Mann’s Der Zauberberg while I did so. During my stay in Dublin, the attacks on the London Underground came quite as a shock, and this also went into the making of my ‘untergrund’ poem, saying the names: “oval, clapham, edgware road” in order to make these places still accessible to me, whatever might happen.

A year later, in June 2006, I happened to be where we are right now, in Rotterdam. There was a reading at the Goethe Institute, presenting an anthology of Dutch and Flemish poetry in German translation, two weeks after Poetry International. There were still posters of the festival all over the place, so I found out I had missed the chance to see Seamus Heaney, and I felt a little bit sad. On my way home I went into the Waterstone’s bookshop in Amsterdam, and there I got myself his new book that made me happy alone by its title, District and Circle, immortalizing another Line of the London Underground, and again I felt some sort of hidden bond between us. There is one poem in this volume that has become my all-time Heaney favorite, it is the last poem of the collection and I would like to read it to you in full.

THE BLACKBIRD OF GLANMORE

On the grass when I arrive,

Filling the stillness with life,

But ready to scare off

At the very first wrong move.

In the ivy when I leave.

It’s you, blackbird, I love.

I park, pause, take heed.

Breathe. Just breathe and sit

And lines I once translated

Come back: ‘I want away

To the house of death, to my father

Und the low clay roof.’

And I think of one gone to him,

A little stillness dancer –

Haunter-son, lost brother –

Cavorting through the yard,

So glad to see me home,

My homesick first term over.

And think of a neighbour’s words

Long after the accident:

‘Yon bird on the shed roof,

Up on the ridge for weeks –

I said nothing at the time

But I never liked yon bird.’

The automatic lock

Clunks shut, the blackbird’s panic

Is shortlived, for a second

I’ve a bird’s eye view of myself,

A shadow on raked gravel

In front of my house of life.

Hedge-hop, I am absolute

For you, your ready talkback,

Your each stand-offish comeback,

Your picky, nervy goldbeak –

On the grass when I arrive,

In the ivy when I leave.

I don’t know how you feel about it, but I think this is utterly beautiful. I love what Heaney does with the sounds, half-rhymes and alliterations, and his own sort of sprung rhythm, not so much inspired by Hopkins, maybe, but rather by the blackbird’s movements that are captured here in an unforgettable way. I am sure that this poem will shine on for a long time; and you don’t need to know about the personal tragedies of the Heaney family, the death of one of Seamus’ younger brothers that is also alluded to in the poem ‘Mid-Term Break’ in Death of a Naturalist from 1966, and you don’t necessarily have to know that Glanmore is the place in County Wicklow where Heaney and his wife lived for some time in the Seventies. But everybody knows the meaning of a death-wish, everybody’s got a father and almost everybody may have seen a blackbird and watched it, and, to say it with Keats, “That is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know” to be touched by this poem.

I fear that time is running out, and I would like to close with my own poem ‘der tollund-mann’ that was written in late 2011, a year and a half after I had seen the real man from the moors in Silkeborg, Jutland, together with my wife Nadja when we returned from a holiday in Norway. We stood there, really watching

his peat-brown head, The mild pods of his eyelids, His pointed skin-cap

and we also bought the catalogue I have here, containing the photographs that were Heaney’s inspiration because, unlike myself, he wrote the poem before seeing the man, but went to see him years later. I had not seen these photographs before seeing the man, but I knew the poem, and this was what made me stop in Jutland. There is one thing to tell, however, before I read the poem, because you may want to know what happened to Stephan. I am sad to say that he died, more than one year ago, and even sadder for me, that we totally fell out of contact years before this happened because of differences other than literary ones. There was no way to talk again, and I did not have the opportunity to tell him either about seeing the Tollund Man, about writing my poem, or about holding a Heaney lecture in Rotterdam. So the only thing left is to remember, and to tell, the driving forces for speech and poetry, wherever you go. As Heaney puts it: “Out there in Jutland / In the old man-killing parishes / I will feel lost, / Unhappy and at home.”

der tollund-mann

man hat ihn nicht im hohen venn gefunden, dem mir von

jugend an bekannten moor; oben in jütland kam der mann

mit dem vom moorwasser gefärbten kurzhaarschnitt samt

bartstoppeln u. augenbrauen aus diesem immer feuchten

grund hervor. torfstecher waren es die ihn fanden, 2 ½ m

unter der erde; torfstecher war er selber auch. der körper

nackt bis auf die lederhaube bis auf den ledergürtel um die

lenden bis auf die lederschlinge um den hals: opferbrauch

der eisenzeit. sie haben ihm noch aug u. mund verschlossen

wie um zu sagen: wir bleiben dir gut; nur daß du sterben

mußtest ging nicht anders. die götter fordern das. du bist

tribut. als wir vor ihm standen rührte er uns wie er dalag

friedvoll ernst ja lieb geradezu. so lange in dem warmen

schoß gelegen. ein nickerchen nach seiner letzten mahlzeit:

brei aus pflanzensamen, wie die pollenanalyse klar ergab.

im späten winter oder frühen frühjahr, am kalten himmel

leuchtet stern um stern .. ich träume manchmal von einem

schmalen steg durchs hohe venn, fängt an zu schneien u.

ich kann nicht sehen wie nahe schon die büschel wollgras

stehen muß immer in die weichen flocken gehen mit meinem

mageninhalt der mich frisch erwärmt .. denn an der straße

steht ein imbißwagen u. leuchtet durch den schnee von fern.

© Norbert Hummelt

Sponsors