Artikel

An introduction to contemporary Chinese poetry

1990: the coming of a silver age

17 april 2014

Many of the non-Misty poets have been influenced by classical Chinese poetry as well as by Western literature, and many younger poets have bypassed the Misty poetry and taken the ancients Qu Yuan, Du Fu, and Tao Yuan-ming or modern poets Bian Zhilin and Mu Dan from the 1940s as their literary ancestors.

New Poetry

Over the past decade, there have been vigorous discussions and passionate debates in China about “One Hundred Years of Chinese New Poetry,” and many questions have been raised, such as “Where is Chinese poetry going?” “Is our poetry getting better or worse?” and “Have we accomplished glorious achievements, like the poets in the Tang dynasty?” Meanwhile, some Western observers have asserted that Chinese contemporary poets have not made the best use of their own traditions.

The New Poetry in China is approximately parallel with literary modernism in Europe and North America. When Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, young free spirits from America, were experimenting with imagery and poetic language in resistance to what they perceived as the deadening Victorian and Georgian styles, the first generation of New Poetry in China employed “plain speech” (or vernacular language) in writing, attempting to wipe out the bookish language from the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) and Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

1912 saw the overthrow of the last dynasty and the birth of the Republic of China. In 1915, when Ezra Pound published his book Cathay featuring some versions of classical Chinese poems, Chinese intellectuals were wholeheartedly promoting Western philosophies. In 1917, when T. S. Eliot published Prufrock and Other Observations in London, Hu Shi (1891–1962) returned to China to teach at Beijing (Peking) University after finishing graduate studies in the United States, and he published eight “free verse” poems that year to promote new thoughts and new language, which marks the beginning of New Poetry in China – a mixed lineage from the very beginning. However, the classical literature and the classical Chinese philosophies Confucianism and Daoism were never abandoned completely but were resurrected again and again throughout the modern and contemporary periods in China.

Hu Shi is generally considered to be one of China’s first modernists, although not the best poet of his time, and his first poetry book of 1920 was the earliest collection of free verse published in China. During the following decades many new poets appeared. Xu Zhimo (1897–1931) studied in the United States and England before returning to China in 1922, when he started the weekly “Modern Review” with Hu Shi and acted as a translator for Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, who visited China in 1924. Xu went to Europe in 1925 and returned to China again in 1927 to found the “New Moon” school of poetry. In his short life span, he introduced a broader variety of English poetry to China, including Thomas Hardy as well as the Romanticists. Wen Yiduo (1899–1946) went to the University of Chicago to study art, then returned to China in 1925 and became an important member of the New Moon school. Li Jinfa (1900–1976) studied in France and brought French Symbolism to China when he published his first poetry book in 1925.

Chinese modernism evolved from the New Moon and Symbolist schools and matured around 1935, with Dai Wangshu (1905–1950) and Bian Zhilin (1910–2000) as leading poets. Other notables include Mu Dan (1918–1977) and Zheng Min (1920– ), who both returned to China after graduate studies in the United States. Ai Qing (1910–1996), father of the internationally renowned dissident artist Ai Weiwei (1957– ), was a work-study student of art in the late 1920s in France, where he was exposed to European modernism, and after coming home in 1932 he became a leading poet in China. Feng Zhi (1905–1993) went to study in Germany in 1930, and after returning to China he translated Rilke’s poetry. The majority of the first generation of New Poetry were poet-translators, and they not only brought Western literature to China but made great contributions to the development of China’s own poetics.

After the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, doors to the West were closed, and official sanctioned poetry of “serving the people” prevailed in mainland China for twenty years, while in the 1950s and 1960s poets such as Luo Fu (1928– ) and Ya Xuan (1932– ) carried on in the modernist mode in Taiwan (and later, in Canada), and Ji Xian (1913–2013 ) continued to write as a Chinese modernist after moving to the United States.

In 1976 another era began in mainland China, represented by the work of Bei Dao, Jiang He, Shu Ting, Gu Cheng, and Yang Lian, who were again emulating the early modernist poetry of the West. These poets were tagged with the term “Misty” by critics in the 1980s; the poets themselves preferred to be called the “Today Group,” acknowledging the role of the journal “Today” (founded in 1978 by Bei Dao and Mang Ke) in gathering together many underground poets of that time.

In the mid-1980s, a “third generation” arose in revolt. Among the avowedly post-Misty poets were Yu Jian (1954– ) and Han Dong (1961– ), who criticized and mocked the lofty tone and lyricism of Misty poetry, promoting instead the use of “spoken language” in contrast with “misty” expressions. Around the same time, feminist poetry became popular, echoing the American female confessional poems that were being introduced through translation. Despite their alternative stance, both the spoken language and feminist poetries bore striking resemblance to Misty poetry, especially the latter in its continuation of a fighting gesture against “patriarchal society.” The protest carnival did not last long. Except for a few who have continued writing poems, most of the Misty and Post-Misty poets have either stopped writing poetry or have not produced interesting poems since late 1990s.

Real changes took place quietly in the 1990s, when poets such as Zhang Shuguang, Sun Wenbo, and Xiao Kaiyu promoted narrative features in poetry, and Zang Di advocated anti-sentimentality, questioning the manner in which Chinese poetry had long been composed. Instead of attacking recent trends, these 1990s innovators ignored the Misty poetry. They re-discovered poets from the 1940s (as T. S. Eliot had re-discovered the metaphysical poets). There was no name for their counter-movement, but in 1999, they (and others, including Xi Chuan and Wang Jiaxin) were accused by the spoken language group of being “poets of intellectual writing,” which for many years had been a derogatory epithet, and as a result these poets have been underrepresented in studies of Chinese poetry. And yet it is this spirit of “intellectual writing” that has been growing in the past twenty years, steadily and forcefully, and this is what has transformed the landscape of contemporary Chinese poetry.

Language And Form

In 1917, the year that Hu Shi introduced free verse to China, T. S. Eliot published his essay “Reflections on Vers Libre,” where he argued that “vers libre does not exist,” because “there is no freedom in art…” Contemporary Chinese poets believe that each poem has its own form.

When Hu Shi promoted free verse as a revolution against the old restraints, he emphasized that “free” would mean a way of writing poetry in contrast with a “classical” way of using rhymes and a strict tonal system. Hu Shi’s first example of free verse was a short essay with line breaks, and his focus was on plain speech or vernacular language. His practice was more of a manifestation than an artistic success*.

In the following decades, the New Moon School promoted a sort of “regulated” verse. Wen Yiduo studied and practiced classical forms before and after his stay in the United States, and he formulated theories for a new “form” of writing. If he had not been killed in 1946 in the wartime, Chinese poetry might have shifted gears. Feng Zhi experimented with Chinese sonnets; Mu Dan explored new syntax and new musicality in free verse writing.

Misty poetry began after the Mao era in China as a rebellion against the established political system and ideologies. These poets won enormous fame internationally, but they did not go far in terms of language innovation or construction of poetics.

In 1994, Chinese poet Zang Di published a groundbreaking essay, “Post-Misty, as a Way of Poetry Writing,” in which he defined 1984 as the end of Misty domination, asserting the significance of new poetic approaches. At the same time he very tactfully pointed out certain limitations of the Post-Misty poetry of the late 1980s.

I agree with Zang Di and many other poets in using Post-Misty as a term for the “third generation.” Furthermore, I use this term to include the spoken language, “Them,” “Not Not,” feminist poetry, and all of those trends or schools that made a big noise in the late 1980s. Other people like to use Post-Misty to include everyone in China who started writing poetry after the 1970s, but this extended use is misleading and gives the impression that the writing of free verse began with the Misty group in 1970s. In actuality contemporary Chinese poets have rediscovered the achievements of 1930s and 1940s New Poetry, which originated in 1917, and many contemporary poets believe that poetry in the 1970s and early 1980s has been overrated, and see the 1990s as the beginning of a new age in Chinese poetry.

The Misty and Post-Misty poets may have succeeded politically and socially, but they failed artistically. And viewed from today’s vantage, the Misty poets resembled the Mao era poets even though they tried to fight against their ideologies. Likewise, the Post-Misty shows strong similarities to the Misty in the anti gestures.

If poetry is “clear expression of mixed feelings” (W. H. Auden), this is what we see: Misty poetry used misty or obscure language to convey clear messages; Post-Misty used clear spoken language to convey clear messages. The generation of the 1990s, however, uses clear and current language (spoken and written) to convey multiple layers of meanings.

It is the non-spoken language poets such as Zang Di, Ya Shi, and Hu Xudong who tend to pick up dynamic jargons from the streets or TV and blend them into unusual syntax, which has infused new vigor into contemporary poetry. It is also the non-spoken language poets who have made more extensive use of classical literature and given that tradition new life. For instance, Duo Duo’s repetition of adverbials is a re-creation of repeated patterns in ancient poetry. Xiao Kaiyu and Jiang Hao frequently turn to classical literature for dictions, tones, and moods – or to be recharged.

An interesting yet ironic phenomenon in the history of contemporary Chinese poetry is that the Misty and post-Misty poetries were never really misty or obscure – they had a clear target to shoot at, government and society. By contrast, the poets of the 1990s and beyond have never been called misty or obscure, yet nobody is able to figure out the true intensions in their writings. For instance, critics have failed to explain what Zang Di was trying to say in one of his earlier poems:

Room and a Plum Tree

There was a moment after all

when the woman in the room was young

standing still before the window of April

On her slim shoulders landed two white pigeons

But perhaps there were no pigeons

It was her branching body

that made us feel the dew-wet tranquility

and hot intestines sprouting from her deep veins

The plum tree bloomed full like stars

illuminating her face with its first flowering

and through her glowing gaze

framed the bluest mystery in that room

房屋与梅树

毕竟存在过那样的时刻

房间里的女人还很年轻

她站立不动在四月的窗前

瘦削的双肩栖落两只白鸽

其实很可能并没有白鸽

而是她那花枝般的姿态

让我们感到露水滋润的安宁

血液凝结就像暗红的辣肠

那些梅花繁星般饱满

把春天最初的盛开移近她的面庞

甚至通过她鲜明的凝神注目

构成那房间里最深湛的秘密

(1984)

Poets and critics saw immediately that this kind of writing was completely different from Misty or Post-Misty. Here poetry was no longer being used as a political or social tool. Not protest, but fascination, or an obsession with the inner nature of things in contrast with outer appearances. Yet many were puzzled as to what this “she” represents. A woman or a tree? Mother or girl friend? Muse? Or poetic form itself? The ambiguity and multiple potentials, the clear and elegant language, the fusion of classical imagery (plum tree and white pigeons) with contemporary experience, and the wild imagination (branching body) – these qualities made people bewildered. Zang Di’s poetry evolved in the early 1990s and became illusionary and difficult. Call this “intellectual” or “academic” writing if you don’t understand its mechanism. That is what the proponents of “spoken language” were doing: attacking poets whose subtleties were hard to comprehend.

In Xiao Kaiyu’s poem “Mao Zedong” (1987), included in this anthology, the emotion was not easy to grasp and the language was classical-sounding. Xiao Kaiyu in the south and Zang Di in the north were hailed as innovators by a small number of poets in China. Like Duo Duo, Zhang Shuguang, Song Lin, and Lü De’an, who also remained in the shadows for many years, Xiao Kaiyu and Zang Di were so private that most readers in China hardly heard of them in the 1980s and early 1990s. They emerged as mature poets in mid-1990s, ten years after other poets of their generation won acclaim in the 1980s. Yet the solid craftsmanship and pioneer spirit of the 1990s poets in “making it new” have influenced more and more poets in contemporary China. What’s new about their poetry is a complexity that had never been seen before in the history of New Poetry, and an innovative syntax that marked the 1990s as a new age – poetry became more poetic when empowered by the use of prose language. Zang Di introduced phrases like “after all,” “therefore,” “as a result,” “in fact,” “even though,” “nevertheless,” and “furthermore” into poetry, making the ordinary and the old sound fresh. This solved problems of language, by loosening up the rigid structures of Misty poetry and tightening up the sloppy structure (or no structure) of Post-Misty. Xiao Kaiyu and Sun Wenbo have supported completeness in thought, in logic, and in sentences, as opposed to the fragmentation often seen in Misty and Post-Misty writing. But even more important than their linguistic innovation is the profound emotion of these poets, combined with an intellectual acuity that’s presented beautifully and subtly.

Many of the poets selected for New Cathay may seem to come from the “intellectual” contingent, but they are not a circle and readers will find in the poems featured here other styles and approaches as well. What these poets share is that they’ve drawn upon a variety of Western trends and also sought to revitalize Chinese traditions, aiming to reinvigorate the New Poetry that originated a century ago.

Chinese-ness

The subtitle of this anthology doesn’t use “Chinese” to refer only to a geographical area or to poetry written in Chinese language (there is more than one language in China), but to a characteristic “Chinese-ness” that traces back to ancient traditions. I will not define what Chinese-ness is, but invite readers to discover its range in meanings by reading through the anthology. This gathering makes an argument that Chinese poems in the past twenty years have been restoring a great legacy, yet in individual ways.

Fragmented sentences and run-on lines are two of the most obvious features Chinese poets learned from the West, and have sometimes overused. The earlier attempt to return to Chinese-ness involved maintaining “completeness” in each line and “wholeness” in each quatrain, as exemplified in the poem “Room and a Plum Tree.”

The poets presented here can’t be easily categorized according to superficially defined “schools” or “movements”; they do show, poet after poet, tremendously varied forms of sensitivity and consciousness, and different ways of reacting to the surrounding world. And in addition to offering a variety of voices in this anthology, I’ve interviewed many of the poets and translated some of their answers here, to let them speak directly to readers about what has happened in China since 1990 and about how they view their traditions and Western influences. These interviews illuminate the time periods through which the poets have lived, serving as complementary introductions to their poems.

Some have criticized Chinese contemporary poets for being too “Westernized” and lacking uniqueness. It is true that poets can be most curious about what is most far away. The Indian poet Tagore didn’t leave long-lasting impressions or influences in China, even though he put his footsteps in the country and was well received. It is the “unfamiliar ghosts” of Europe and America that have haunted Chinese poets the most – the imagination of the “Other.” And this has been mutual. T. S. Eliot, who influenced Chinese poets to an enormous degree, was influenced by Baudelaire, who in turn had been influenced by Li Bai. Twentieth-century American poetry has likewise been filled with “Oriental” allusions and imagery and with the stylistic influences of ancient Chinese nature poetry. Chinese poets recognize their own blood coursing through the bodies of others.

Several authors featured here say in the accompanying interviews that they are not afraid of losing an “individual voice,” emphasizing that they welcome influences and exchange. As Zang Di says, “Chinese New Poetry started with Walt Whitman inhabiting Bian Zhilin’s body.” Wang Jiaxin, Hu Xudong, and others have built personal aesthetics and kinship through translating foreign poetry. And the young poet Jiang Li predicts that “the Chinese–Western fusion will be an important part of Chinese poetry in the years to come.” These poets choose in their writings to have a dialogue with poets from other countries and eras. If Shakespeare could write about old Danish legends, why can’t Chinese poets write about American or Spanish stories? The resulting “foreignness” can make their poetry even more Chinese. Or, to reverse the cliché: the more international, the more local. Or to borrow T.S. Eliot’s phrase, the division between classical poetry and New Poetry does not exist: there is only good poetry, bad poetry, and chaos.

Like the poet-translators from the 1920s to 1940s, these new poets view translation as part of their own creative writing. If Ezra Pound “re-invented” Chinese poetry, they have re-invented English, French, German, Russian, Arabic, Spanish, Portuguese poetry – you name it.

I don’t want to seem to over-defend the poets in my home country, but I do want to point out that they’ve inherited many reputedly “foreign” features from the homemade classical literature. For instance, a poem of dramatic monologue may seem to copy Robert Browning or T. S. Eliot but actually follow ancient poems such as “Chang Gan Xing” (or “River Merchant’s Wife: A Letter”). Narrative forms may look like they’ve been learned from Anglo-American poetry, but tell me which poem from The Book of Songs isn’t narrative?

From emulating Western poetry in the 1970s and 1980s, to blending the Western-Chinese modes and expanding the boundaries of poetic expressions in the 1990s, Chinese poetry has been progressing artistically as well as linguistically. Some of the misty and post-misty poets also produced their best work in the 1990s before declining in the new century.

It is for the aesthetic vitality and maturity of Chinese poetry since 1990 that this period may be considered a Silver Age, as we perceive the time of The Book of Songs as a Bronze Age and the Tang Dynasty as a Golden Age. Personally I find the past two decades more interesting than even the high Tang, but to call this a Silver Age is to save room for perfection.

Coincidentally or not, many of the contemporary Chinese poets take the Russian poets of the Silver Age as their kin and soul mates. Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva, Akhmatova, and Pasternak did not belong to any school or faction, and together their works comprised a Silver Age achievement. Similarly, Duo Duo, Zang Di, Xiao Kaiyu, Zhang Shuguang, Sun Wenbo, Ya Shi, Jiang Tao, Hu Xutong, and many others do not belong to any school or group either; these are ambitious poets who have made great efforts to change the nature of contemporary Chinese poetry, and through the cumulative impact of their individual writing, we see how Chinese poetry has evolved.

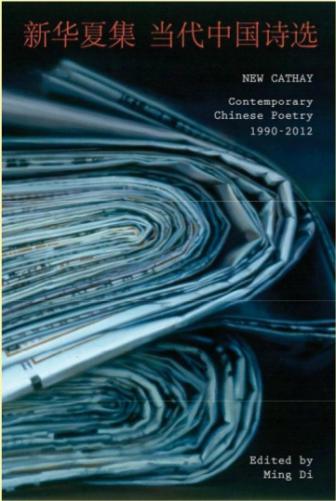

The above article is an excerpt from the Preface of New Cathay: Contemporary Chinese Poetry, edited by Ming Di (North Adams, USA: Tupelo Press. 2013)

Author's note: I’ve changed my opinion on the merit of Hu Shi’s first attempt of free verse in 1916 which I now believe is better than the eight poems he published in 1917. This is discussed in the introduction of Chinese Feature in the 2014 issue of Poetry International jounral by San Diego State University in USA.

Over the course of three thousand years of Chinese poetry, tremendous changes have taken place at certain times, especially in 1917, the year that breaks Chinese poetry into two worlds: classical and modern. But in the past two decades, poets in China have been trying, after many years of influence from the West, to “return” to ancient literary traditions. However, this burgeoning renaissance doesn’t mean to write exactly the way poetry was written in the distant past, but to re-explore the legacy of the breadth of Chinese literature and to adopt a classical “spirit” in perspectives and emotional appeals. What makes the story more complicated is that there are many different eras and modes to which contemporary Chinese poets may try to return. Some see exemplars in the Tang or Song dynasties, and some prefer the poetry of Chu, whereas others admire the simplicity and lively cadences in the Book of Songs, a gathering of poems from the eleventh to sixth century BCE, the first Chinese anthology.

While poetry from the Tang dynasty (about 618–907 CE) has been introduced into English through translations in great abundance, there has been little translation of the poetry by Qu Yuan (343–278 BCE), from the State of Chu, the first known poet of ancient China. Likewise, although there have been numerous translations of what is called “Misty” poetry (since the 1970s) and Post-Misty poetry (since the mid-1980s), other approaches outside the Misty/Post-Misty trends have barely been introduced, and certainly not in depth, with genuinely poetic presentations.Many of the non-Misty poets have been influenced by classical Chinese poetry as well as by Western literature, and many younger poets have bypassed the Misty poetry and taken the ancients Qu Yuan, Du Fu, and Tao Yuan-ming or modern poets Bian Zhilin and Mu Dan from the 1940s as their literary ancestors.

New Poetry

Over the past decade, there have been vigorous discussions and passionate debates in China about “One Hundred Years of Chinese New Poetry,” and many questions have been raised, such as “Where is Chinese poetry going?” “Is our poetry getting better or worse?” and “Have we accomplished glorious achievements, like the poets in the Tang dynasty?” Meanwhile, some Western observers have asserted that Chinese contemporary poets have not made the best use of their own traditions.

The New Poetry in China is approximately parallel with literary modernism in Europe and North America. When Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, young free spirits from America, were experimenting with imagery and poetic language in resistance to what they perceived as the deadening Victorian and Georgian styles, the first generation of New Poetry in China employed “plain speech” (or vernacular language) in writing, attempting to wipe out the bookish language from the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) and Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

1912 saw the overthrow of the last dynasty and the birth of the Republic of China. In 1915, when Ezra Pound published his book Cathay featuring some versions of classical Chinese poems, Chinese intellectuals were wholeheartedly promoting Western philosophies. In 1917, when T. S. Eliot published Prufrock and Other Observations in London, Hu Shi (1891–1962) returned to China to teach at Beijing (Peking) University after finishing graduate studies in the United States, and he published eight “free verse” poems that year to promote new thoughts and new language, which marks the beginning of New Poetry in China – a mixed lineage from the very beginning. However, the classical literature and the classical Chinese philosophies Confucianism and Daoism were never abandoned completely but were resurrected again and again throughout the modern and contemporary periods in China.

Hu Shi is generally considered to be one of China’s first modernists, although not the best poet of his time, and his first poetry book of 1920 was the earliest collection of free verse published in China. During the following decades many new poets appeared. Xu Zhimo (1897–1931) studied in the United States and England before returning to China in 1922, when he started the weekly “Modern Review” with Hu Shi and acted as a translator for Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, who visited China in 1924. Xu went to Europe in 1925 and returned to China again in 1927 to found the “New Moon” school of poetry. In his short life span, he introduced a broader variety of English poetry to China, including Thomas Hardy as well as the Romanticists. Wen Yiduo (1899–1946) went to the University of Chicago to study art, then returned to China in 1925 and became an important member of the New Moon school. Li Jinfa (1900–1976) studied in France and brought French Symbolism to China when he published his first poetry book in 1925.

Chinese modernism evolved from the New Moon and Symbolist schools and matured around 1935, with Dai Wangshu (1905–1950) and Bian Zhilin (1910–2000) as leading poets. Other notables include Mu Dan (1918–1977) and Zheng Min (1920– ), who both returned to China after graduate studies in the United States. Ai Qing (1910–1996), father of the internationally renowned dissident artist Ai Weiwei (1957– ), was a work-study student of art in the late 1920s in France, where he was exposed to European modernism, and after coming home in 1932 he became a leading poet in China. Feng Zhi (1905–1993) went to study in Germany in 1930, and after returning to China he translated Rilke’s poetry. The majority of the first generation of New Poetry were poet-translators, and they not only brought Western literature to China but made great contributions to the development of China’s own poetics.

After the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, doors to the West were closed, and official sanctioned poetry of “serving the people” prevailed in mainland China for twenty years, while in the 1950s and 1960s poets such as Luo Fu (1928– ) and Ya Xuan (1932– ) carried on in the modernist mode in Taiwan (and later, in Canada), and Ji Xian (1913–2013 ) continued to write as a Chinese modernist after moving to the United States.

In 1976 another era began in mainland China, represented by the work of Bei Dao, Jiang He, Shu Ting, Gu Cheng, and Yang Lian, who were again emulating the early modernist poetry of the West. These poets were tagged with the term “Misty” by critics in the 1980s; the poets themselves preferred to be called the “Today Group,” acknowledging the role of the journal “Today” (founded in 1978 by Bei Dao and Mang Ke) in gathering together many underground poets of that time.

In the mid-1980s, a “third generation” arose in revolt. Among the avowedly post-Misty poets were Yu Jian (1954– ) and Han Dong (1961– ), who criticized and mocked the lofty tone and lyricism of Misty poetry, promoting instead the use of “spoken language” in contrast with “misty” expressions. Around the same time, feminist poetry became popular, echoing the American female confessional poems that were being introduced through translation. Despite their alternative stance, both the spoken language and feminist poetries bore striking resemblance to Misty poetry, especially the latter in its continuation of a fighting gesture against “patriarchal society.” The protest carnival did not last long. Except for a few who have continued writing poems, most of the Misty and Post-Misty poets have either stopped writing poetry or have not produced interesting poems since late 1990s.

Real changes took place quietly in the 1990s, when poets such as Zhang Shuguang, Sun Wenbo, and Xiao Kaiyu promoted narrative features in poetry, and Zang Di advocated anti-sentimentality, questioning the manner in which Chinese poetry had long been composed. Instead of attacking recent trends, these 1990s innovators ignored the Misty poetry. They re-discovered poets from the 1940s (as T. S. Eliot had re-discovered the metaphysical poets). There was no name for their counter-movement, but in 1999, they (and others, including Xi Chuan and Wang Jiaxin) were accused by the spoken language group of being “poets of intellectual writing,” which for many years had been a derogatory epithet, and as a result these poets have been underrepresented in studies of Chinese poetry. And yet it is this spirit of “intellectual writing” that has been growing in the past twenty years, steadily and forcefully, and this is what has transformed the landscape of contemporary Chinese poetry.

Language And Form

In 1917, the year that Hu Shi introduced free verse to China, T. S. Eliot published his essay “Reflections on Vers Libre,” where he argued that “vers libre does not exist,” because “there is no freedom in art…” Contemporary Chinese poets believe that each poem has its own form.

When Hu Shi promoted free verse as a revolution against the old restraints, he emphasized that “free” would mean a way of writing poetry in contrast with a “classical” way of using rhymes and a strict tonal system. Hu Shi’s first example of free verse was a short essay with line breaks, and his focus was on plain speech or vernacular language. His practice was more of a manifestation than an artistic success*.

In the following decades, the New Moon School promoted a sort of “regulated” verse. Wen Yiduo studied and practiced classical forms before and after his stay in the United States, and he formulated theories for a new “form” of writing. If he had not been killed in 1946 in the wartime, Chinese poetry might have shifted gears. Feng Zhi experimented with Chinese sonnets; Mu Dan explored new syntax and new musicality in free verse writing.

Misty poetry began after the Mao era in China as a rebellion against the established political system and ideologies. These poets won enormous fame internationally, but they did not go far in terms of language innovation or construction of poetics.

In 1994, Chinese poet Zang Di published a groundbreaking essay, “Post-Misty, as a Way of Poetry Writing,” in which he defined 1984 as the end of Misty domination, asserting the significance of new poetic approaches. At the same time he very tactfully pointed out certain limitations of the Post-Misty poetry of the late 1980s.

I agree with Zang Di and many other poets in using Post-Misty as a term for the “third generation.” Furthermore, I use this term to include the spoken language, “Them,” “Not Not,” feminist poetry, and all of those trends or schools that made a big noise in the late 1980s. Other people like to use Post-Misty to include everyone in China who started writing poetry after the 1970s, but this extended use is misleading and gives the impression that the writing of free verse began with the Misty group in 1970s. In actuality contemporary Chinese poets have rediscovered the achievements of 1930s and 1940s New Poetry, which originated in 1917, and many contemporary poets believe that poetry in the 1970s and early 1980s has been overrated, and see the 1990s as the beginning of a new age in Chinese poetry.

The Misty and Post-Misty poets may have succeeded politically and socially, but they failed artistically. And viewed from today’s vantage, the Misty poets resembled the Mao era poets even though they tried to fight against their ideologies. Likewise, the Post-Misty shows strong similarities to the Misty in the anti gestures.

If poetry is “clear expression of mixed feelings” (W. H. Auden), this is what we see: Misty poetry used misty or obscure language to convey clear messages; Post-Misty used clear spoken language to convey clear messages. The generation of the 1990s, however, uses clear and current language (spoken and written) to convey multiple layers of meanings.

It is the non-spoken language poets such as Zang Di, Ya Shi, and Hu Xudong who tend to pick up dynamic jargons from the streets or TV and blend them into unusual syntax, which has infused new vigor into contemporary poetry. It is also the non-spoken language poets who have made more extensive use of classical literature and given that tradition new life. For instance, Duo Duo’s repetition of adverbials is a re-creation of repeated patterns in ancient poetry. Xiao Kaiyu and Jiang Hao frequently turn to classical literature for dictions, tones, and moods – or to be recharged.

An interesting yet ironic phenomenon in the history of contemporary Chinese poetry is that the Misty and post-Misty poetries were never really misty or obscure – they had a clear target to shoot at, government and society. By contrast, the poets of the 1990s and beyond have never been called misty or obscure, yet nobody is able to figure out the true intensions in their writings. For instance, critics have failed to explain what Zang Di was trying to say in one of his earlier poems:

Room and a Plum Tree

There was a moment after all

when the woman in the room was young

standing still before the window of April

On her slim shoulders landed two white pigeons

But perhaps there were no pigeons

It was her branching body

that made us feel the dew-wet tranquility

and hot intestines sprouting from her deep veins

The plum tree bloomed full like stars

illuminating her face with its first flowering

and through her glowing gaze

framed the bluest mystery in that room

房屋与梅树

毕竟存在过那样的时刻

房间里的女人还很年轻

她站立不动在四月的窗前

瘦削的双肩栖落两只白鸽

其实很可能并没有白鸽

而是她那花枝般的姿态

让我们感到露水滋润的安宁

血液凝结就像暗红的辣肠

那些梅花繁星般饱满

把春天最初的盛开移近她的面庞

甚至通过她鲜明的凝神注目

构成那房间里最深湛的秘密

(1984)

Poets and critics saw immediately that this kind of writing was completely different from Misty or Post-Misty. Here poetry was no longer being used as a political or social tool. Not protest, but fascination, or an obsession with the inner nature of things in contrast with outer appearances. Yet many were puzzled as to what this “she” represents. A woman or a tree? Mother or girl friend? Muse? Or poetic form itself? The ambiguity and multiple potentials, the clear and elegant language, the fusion of classical imagery (plum tree and white pigeons) with contemporary experience, and the wild imagination (branching body) – these qualities made people bewildered. Zang Di’s poetry evolved in the early 1990s and became illusionary and difficult. Call this “intellectual” or “academic” writing if you don’t understand its mechanism. That is what the proponents of “spoken language” were doing: attacking poets whose subtleties were hard to comprehend.

In Xiao Kaiyu’s poem “Mao Zedong” (1987), included in this anthology, the emotion was not easy to grasp and the language was classical-sounding. Xiao Kaiyu in the south and Zang Di in the north were hailed as innovators by a small number of poets in China. Like Duo Duo, Zhang Shuguang, Song Lin, and Lü De’an, who also remained in the shadows for many years, Xiao Kaiyu and Zang Di were so private that most readers in China hardly heard of them in the 1980s and early 1990s. They emerged as mature poets in mid-1990s, ten years after other poets of their generation won acclaim in the 1980s. Yet the solid craftsmanship and pioneer spirit of the 1990s poets in “making it new” have influenced more and more poets in contemporary China. What’s new about their poetry is a complexity that had never been seen before in the history of New Poetry, and an innovative syntax that marked the 1990s as a new age – poetry became more poetic when empowered by the use of prose language. Zang Di introduced phrases like “after all,” “therefore,” “as a result,” “in fact,” “even though,” “nevertheless,” and “furthermore” into poetry, making the ordinary and the old sound fresh. This solved problems of language, by loosening up the rigid structures of Misty poetry and tightening up the sloppy structure (or no structure) of Post-Misty. Xiao Kaiyu and Sun Wenbo have supported completeness in thought, in logic, and in sentences, as opposed to the fragmentation often seen in Misty and Post-Misty writing. But even more important than their linguistic innovation is the profound emotion of these poets, combined with an intellectual acuity that’s presented beautifully and subtly.

Many of the poets selected for New Cathay may seem to come from the “intellectual” contingent, but they are not a circle and readers will find in the poems featured here other styles and approaches as well. What these poets share is that they’ve drawn upon a variety of Western trends and also sought to revitalize Chinese traditions, aiming to reinvigorate the New Poetry that originated a century ago.

Chinese-ness

The subtitle of this anthology doesn’t use “Chinese” to refer only to a geographical area or to poetry written in Chinese language (there is more than one language in China), but to a characteristic “Chinese-ness” that traces back to ancient traditions. I will not define what Chinese-ness is, but invite readers to discover its range in meanings by reading through the anthology. This gathering makes an argument that Chinese poems in the past twenty years have been restoring a great legacy, yet in individual ways.

Fragmented sentences and run-on lines are two of the most obvious features Chinese poets learned from the West, and have sometimes overused. The earlier attempt to return to Chinese-ness involved maintaining “completeness” in each line and “wholeness” in each quatrain, as exemplified in the poem “Room and a Plum Tree.”

The poets presented here can’t be easily categorized according to superficially defined “schools” or “movements”; they do show, poet after poet, tremendously varied forms of sensitivity and consciousness, and different ways of reacting to the surrounding world. And in addition to offering a variety of voices in this anthology, I’ve interviewed many of the poets and translated some of their answers here, to let them speak directly to readers about what has happened in China since 1990 and about how they view their traditions and Western influences. These interviews illuminate the time periods through which the poets have lived, serving as complementary introductions to their poems.

Some have criticized Chinese contemporary poets for being too “Westernized” and lacking uniqueness. It is true that poets can be most curious about what is most far away. The Indian poet Tagore didn’t leave long-lasting impressions or influences in China, even though he put his footsteps in the country and was well received. It is the “unfamiliar ghosts” of Europe and America that have haunted Chinese poets the most – the imagination of the “Other.” And this has been mutual. T. S. Eliot, who influenced Chinese poets to an enormous degree, was influenced by Baudelaire, who in turn had been influenced by Li Bai. Twentieth-century American poetry has likewise been filled with “Oriental” allusions and imagery and with the stylistic influences of ancient Chinese nature poetry. Chinese poets recognize their own blood coursing through the bodies of others.

Several authors featured here say in the accompanying interviews that they are not afraid of losing an “individual voice,” emphasizing that they welcome influences and exchange. As Zang Di says, “Chinese New Poetry started with Walt Whitman inhabiting Bian Zhilin’s body.” Wang Jiaxin, Hu Xudong, and others have built personal aesthetics and kinship through translating foreign poetry. And the young poet Jiang Li predicts that “the Chinese–Western fusion will be an important part of Chinese poetry in the years to come.” These poets choose in their writings to have a dialogue with poets from other countries and eras. If Shakespeare could write about old Danish legends, why can’t Chinese poets write about American or Spanish stories? The resulting “foreignness” can make their poetry even more Chinese. Or, to reverse the cliché: the more international, the more local. Or to borrow T.S. Eliot’s phrase, the division between classical poetry and New Poetry does not exist: there is only good poetry, bad poetry, and chaos.

Like the poet-translators from the 1920s to 1940s, these new poets view translation as part of their own creative writing. If Ezra Pound “re-invented” Chinese poetry, they have re-invented English, French, German, Russian, Arabic, Spanish, Portuguese poetry – you name it.

I don’t want to seem to over-defend the poets in my home country, but I do want to point out that they’ve inherited many reputedly “foreign” features from the homemade classical literature. For instance, a poem of dramatic monologue may seem to copy Robert Browning or T. S. Eliot but actually follow ancient poems such as “Chang Gan Xing” (or “River Merchant’s Wife: A Letter”). Narrative forms may look like they’ve been learned from Anglo-American poetry, but tell me which poem from The Book of Songs isn’t narrative?

From emulating Western poetry in the 1970s and 1980s, to blending the Western-Chinese modes and expanding the boundaries of poetic expressions in the 1990s, Chinese poetry has been progressing artistically as well as linguistically. Some of the misty and post-misty poets also produced their best work in the 1990s before declining in the new century.

It is for the aesthetic vitality and maturity of Chinese poetry since 1990 that this period may be considered a Silver Age, as we perceive the time of The Book of Songs as a Bronze Age and the Tang Dynasty as a Golden Age. Personally I find the past two decades more interesting than even the high Tang, but to call this a Silver Age is to save room for perfection.

Coincidentally or not, many of the contemporary Chinese poets take the Russian poets of the Silver Age as their kin and soul mates. Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva, Akhmatova, and Pasternak did not belong to any school or faction, and together their works comprised a Silver Age achievement. Similarly, Duo Duo, Zang Di, Xiao Kaiyu, Zhang Shuguang, Sun Wenbo, Ya Shi, Jiang Tao, Hu Xutong, and many others do not belong to any school or group either; these are ambitious poets who have made great efforts to change the nature of contemporary Chinese poetry, and through the cumulative impact of their individual writing, we see how Chinese poetry has evolved.

The above article is an excerpt from the Preface of New Cathay: Contemporary Chinese Poetry, edited by Ming Di (North Adams, USA: Tupelo Press. 2013)

Author's note: I’ve changed my opinion on the merit of Hu Shi’s first attempt of free verse in 1916 which I now believe is better than the eight poems he published in 1917. This is discussed in the introduction of Chinese Feature in the 2014 issue of Poetry International jounral by San Diego State University in USA.

© Ming Di

Bron: New Cathay: Contemporary Chinese Poetry, edited by Ming Di (Tupelo Press, co-published by Poetry Foundation, USA, 2013)

Sponsors

Partners

LantarenVenster – Verhalenhuis Belvédère