The place of poetry

In what places does poetry occur? If its most natural habitat is the area of language annexed or leased by a poem, what area is that?

Poetry’s place is in language. Because this particular art utilises one of the most common tools of communication—language—it can take the form of a message, which sometimes confuses those readers looking for direct meaning. Poetry is everywhere because language is everywhere, but not all language is poetry. Everywhere you look you see language: in the worlds of science and psychoanalysis, of oil drillers and pavers, in the toy shop selling Lego and the financial department of the bordello across the street. This does not mean poetry necessarily belongs in these domains: poetry only exists within the language itself.

Does poetry occupy its own place or has it moved to another ‘seat’? Or has its seat has been taken by something else – science, deconstructionism, psychoanalysis?

The role (and the place) of poetry in Colombia, China, or Nigeria is not the same as it is in my home in the Netherlands. I do a lot of travelling around the world, and I see that the role of poetry is different in every country. From the ‘most individual expression of the most individual emotion’ found at the back of a bookshop to the most one-dimensional message on the front page of a newspaper. From the thundering manifesto in the hands of an angry mob to the impenetrable linguistic constructions penned by a handful of insiders. Poetry’s role and position is largely decided by the location of its audience.

Is it at all possible for a poem that has immigrated to another language to feel at home there?

At a large festival in Colombia I met a poet, a young girl from an African country. From the time she was twelve to the time she was sixteen she was forced to gun down other groups of children her age with a Kalashnikov. When she was sixteen she cast the weapon to the ground and, at great risk to her own life, decided to write poetry. She was invited to read this poetry, in which she grapples with her past, at the festival, and with her story she touched the hearts of ten thousand Colombians. This story unfortunately never quite became poetry. The Colombians interpreted it as poetry because they were moved by it, and threatened me with lynching when I, with my Western viewpoint, disagreed with their interpretation.

Here, sitting in Rotterdam, that memory leaves me with mixed feelings. On the one hand is my disdain for poetry as a thundering, political manifesto, and on the other hand is my jealousy of countries where writing poetry is dangerous.

Is poetry’s role changing? Definitely. The current discussion in the Netherlands about public engagement with poetry has gone on for longer than anyone can remember, and the consensus is different every time the topic comes up. Poetry changes because language changes; because society changes, and because poets change. For example, in many countries good poetry is timeless and universal, not tied to everyday realities. If there’s a hurricane in Haiti, journalists write about it—not poets. However touching and personal these journalistic reports may be, after a few days the text and the paper are at the bottom of the litter box. Then people invite a poet like the Jamaican Kwame Dawes to write about the situation in Haiti. Because Kwame Dawes is a good poet, his poem is read for decades after it is published, and keeps the memory of these events alive in a unique way.

Do I like journalistic poetry? No. I don’t feel like that’s really poetry’s job. Do I like Dawes’s poem about Haiti? Absolutely, because it’s poetry.

What function do poetry festivals play? Is there any danger that their public aspects (for instance public readings, meetings with poets, this whole inevitable theatricalisation) might overshadow the poem itself? To what extent is the reception of a text influenced by the space in which a literary event is held?

When a poem is transplanted into another language it loses something and gains something. Naturally a translated poem is not the same as the original poem. If we’re lucky it’s a new poem, or it can represent and reproduce a large part of the original in a new language. A new setting always results in a relevant poetic experience in one way or another. The reader is revealed and the sounds of the original language ring through, strengthened by elements in the new language.

This is the unique role of international poetry festivals. At a poetry festival you don’t look for a familiar experience, where poetry is absorbed in the personal space of one’s own language. Instead you look for an equally relevant but fundamentally different experience. This new experience is based on encounters, whether with another language and culture, with poets, with like-minded people, and with all the images, thoughts, associations, confusion, and inspiration that the unknown offers. Of course the poetry is influenced by the fact that the poet is up on a stage with a lamp pointed at his head, and that you are listening in a darkened hall surrounded by other people. It would also influence the poetry if the poet personally whispered it in your ear at night, or if you met the poem on the haunches of a passing train.

Is a poetry festival capable of shaping the cultural landscape of a city?

Let me give you an example from a project in Rotterdam. For 25 years we’ve distilled lines from poems written by our international festival guests, and we put some of these on the city’s garbage trucks. Every day poetry is out on the streets of Rotterdam, in every neighbourhood. These poems get the city’s population thinking, and invite them into a dialogue. International poetry connects the city’s residents to each other, to the garbage collectors, and to the poetry of other cultures. It makes them proud of their city: a place where it is logical for poetry and rubbish to come together. This project allows people to become comfortable with poetry in the public sphere.

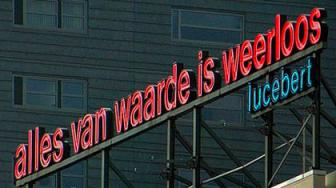

In the 1970s my organisation put the line ‘Everything valuable is vulnerable’ on a bank in neon letters. It was selected from a poem by the Dutch poet Lucebert. The line is still there, and is warmly embraced by the entire community, regardless of their engagement with poetry, and regardless of their home country. In Rotterdam poetry unites the population—a population built up of roughly 175 different cultures.

What are poetry’s ‘soft spots’?

Everything valuable is vulnerable, and that’s certainly true of poetry. You can’t eat it, you can’t wrap it around you when you’re cold, and you can’t take shelter under it during a rainstorm. Poetry in book form has seen hard times. In our culture, where a product’s success is contingent on quantity, poetry collections are in danger. In the Netherlands we print 700 copies of a successful poet’s work. 200 copies go to the publisher, to the press, and to various friends, 200 collect dust under the poet’s bed, and 300 go to the bookshops, where about 150 are actually sold. When the continued existence of the publisher and the bookseller is dependent on each publication, the collection disappears and poetry moves from book to stage.

Populism has dominated the field here in recent years. Poetry is traditionally the domain of the elite, and is seen by the country’s dominant political party as arrogant. It’s as though every poem says to them: if you don’t understand this you are stupid. Many voices are calling for the collective neck-wringing of artistic expressions like poetry; the only art that is permitted is art that pays for itself. It’s really up to poetry to offer a rebuttal to this idea, and this may mean that poetry needs to rediscover itself. Poetry in the city’s public spaces and poetry on the stage are good examples of ways this is happening right now.

Sponsors